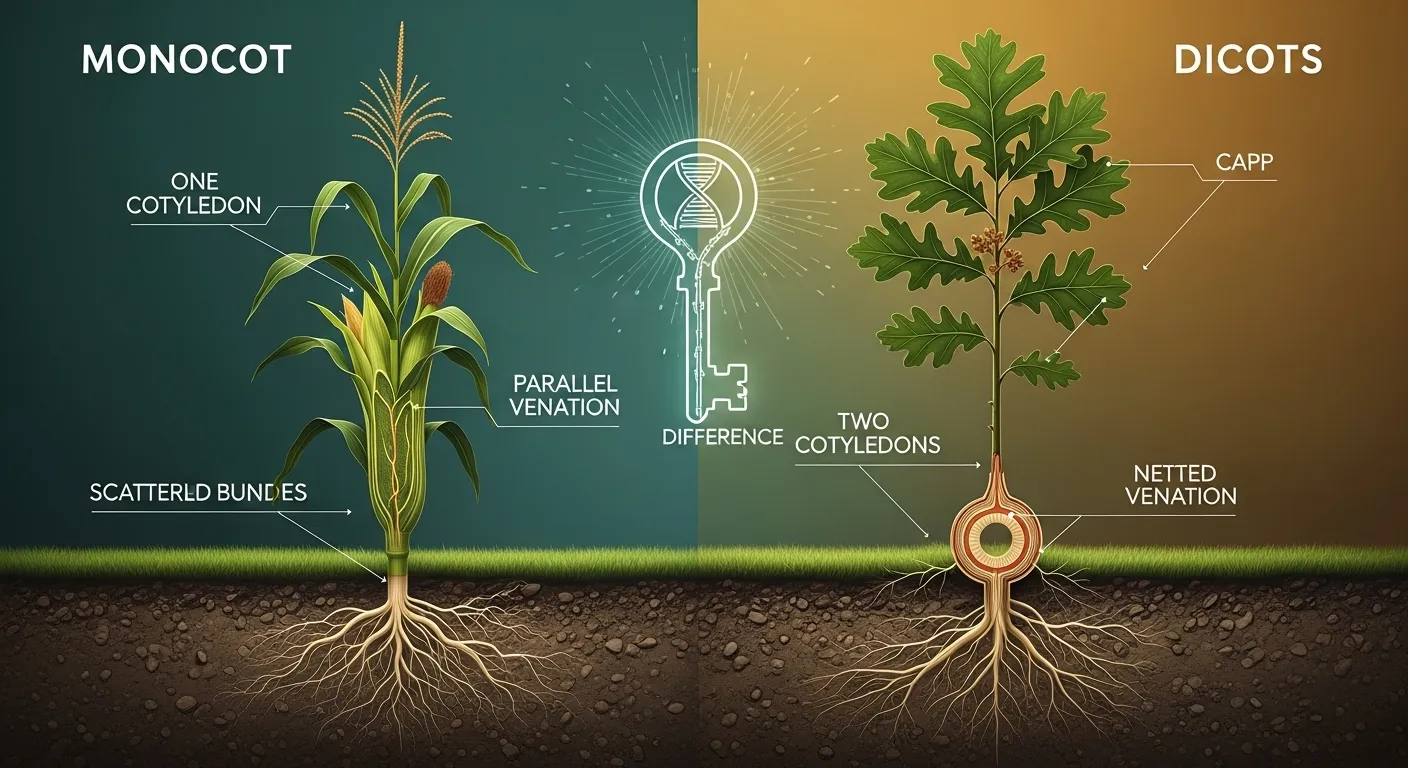

The difference between monocot and dicot plants is one of the first and most enduring distinctions students learn in botany. Understanding this difference helps identify plants in the field, explains how plants grow, and clarifies why some species behave differently in agriculture and ecology. In this article we’ll break down the key structural, developmental, and evolutionary contrasts between these two major groups, with clear, practical guidance for identification and application. Fundamental Overview: What are Monocots and Dicots? Monocots and dicots are informal terms historically used to separate flowering plants (angiosperms) based on the number of cotyledons (seed leaves) present in the embryo. Monocots typically have one cotyledon, while dicots have two. Although modern phylogenetics has refined how botanists classify angiosperms, the monocot–dicot distinction remains highly useful for practical identification. These two groups diverged early in angiosperm evolution, and their morphological differences affect nearly every organ system: seeds, stems, leaves, roots, flowers, and even pollen. The distinction helps explain variations in crop management (for example, how grasses respond to mowing vs. legumes) and ecological roles (such as grassland vs. deciduous forest dynamics). For SEO and clarity, note that people commonly search phrases like “monocot vs dicot characteristics,” “how to tell monocot from dicot,” and the exact phrase discussed here—difference between monocot and dicot plants—so this article addresses common queries and practical uses of these distinctions. 1. Definition and origin of terms The terms monocotyledon (monocot) and dicotyledon (dicot) come from Greek: mono = one, di = two, and cotyledon = seed leaf. Historically, botanists grouped flowering plants into these two categories purely by cotyledon number. This classification worked well because cotyledon number correlates with many other structural differences. Later molecular studies showed that “dicots” are a paraphyletic group (not all descendants from a single ancestor are included), which led to a refined set of clades (e.g., eudicots) in modern taxonomy. Despite this, for everyday identification and agricultural contexts the monocot/dicot framework remains practical and widely taught. 2. Why the difference matters Recognizing whether a plant is a monocot or dicot helps predict growth patterns, responses to stress, and suitable cultivation techniques. For example, monocot grasses—like wheat and rice—have fibrous roots and parallel leaf veins, making them resilient to grazing and surface disturbance. Dicots—such as beans and tomatoes—commonly develop taproots and netted leaves, which influence irrigation, fertilization, and pruning decisions. From an ecological standpoint, the distributions of monocot- and dicot-dominated habitats (lawns and grasslands vs. forests and shrublands) shape soil processes, fire regimes, and animal communities. Thus the monocot–dicot distinction is not just academic; it underpins practical choices in land management and crop breeding. Seed and Embryo: Cotyledons and Germination Seed structure is the most immediate and definitive feature used to separate monocots from dicots. The number and function of cotyledons affect early nutrient mobilization and seedling form. Both groups store nutrients differently: some store in the seed endosperm, others in the cotyledons. These storage strategies influence how seedlings emerge and which part of the embryo becomes photosynthetic first. Seed anatomy also influences germination behavior—some seedlings break the seed coat above ground, others below ground. Understanding these differences helps gardeners, farmers, and ecologists manage seedlings more effectively. 3. Cotyledon number and seed anatomy Monocot seeds usually have a single cotyledon that often functions primarily to absorb nutrients from the endosperm and deliver them to the developing seedling. In grasses, the cotyledon is modified into structures such as the scutellum (in cereals) that facilitate nutrient transfer during germination. Dicot seeds contain two cotyledons that typically act as storage organs and may become the first photosynthetic leaves in the seedling. These two seed leaves often store significant reserves and can be thick or fleshy depending on species, influencing how long seedlings rely on stored food before photosynthesis begins. Because cotyledon morphology can vary, cotyledon count is most reliable when seeds or newly germinated seedlings are available. For mature plants, other traits (leaves, stems, roots) are used for identification. 4. Germination patterns and seedling traits Monocot seedlings often exhibit a growth pattern known as hypogeal or epigeal depending on species, but many grasses show a protective sheath (coleoptile) that pushes through soil to protect the shoot. Roots emerge from a basal meristem area; cotyledon may stay below ground or be non-photosynthetic. Dicot seedlings frequently produce a distinct above-ground pair of cotyledons that unfold and photosynthesize until true leaves take over. The presence of a central primary root (taproot) is common in dicots, giving seedlings immediate access to deeper soil moisture. These differences influence planting depth and seed care: monocot seeds (e.g., corn) often require consistent shallow planting and surface moisture, while some dicot seeds may tolerate slightly deeper placement and variable moisture because of their stored reserves. Vegetative Differences: Roots, Stems, and Leaves Vegetative anatomy is where differences become obvious even without observing seeds. Root architecture, stem vascular arrangement, and leaf venation are key diagnostic traits. Leaves and stems determine how a plant transports water, nutrients, and sugars, and they influence tolerance to physical damage, drought, and herbivory. Recognizing these patterns allows rapid field identification. Below are the classic contrasts that students and practitioners use to tell monocots from dicots. 5. Root systems Monocots typically develop a fibrous root system: many similarly sized roots arise from the stem base. This network stabilizes soil and is efficient at exploiting surface nutrients and moisture, which is why grasses recover quickly after cutting. Dicots usually form a taproot system—a dominant primary root that grows downward with lateral branches. This allows access to deeper water and nutrients and can confer drought resilience. Many dicots also produce specialized storage roots (e.g., carrots). Root anatomy differences also reflect secondary growth potential (discussed later): dicot roots more commonly undergo cambial activity leading to thickening in woody species. 6. Stem vascular arrangement In monocots, vascular bundles (xylem and phloem) are scattered throughout the stem cross-section; they often lack a continuous ring. This arrangement typically precludes extensive secondary thickening and explains why most monocots are herbaceous (non-woody). Dicot stems display vascular bundles arranged