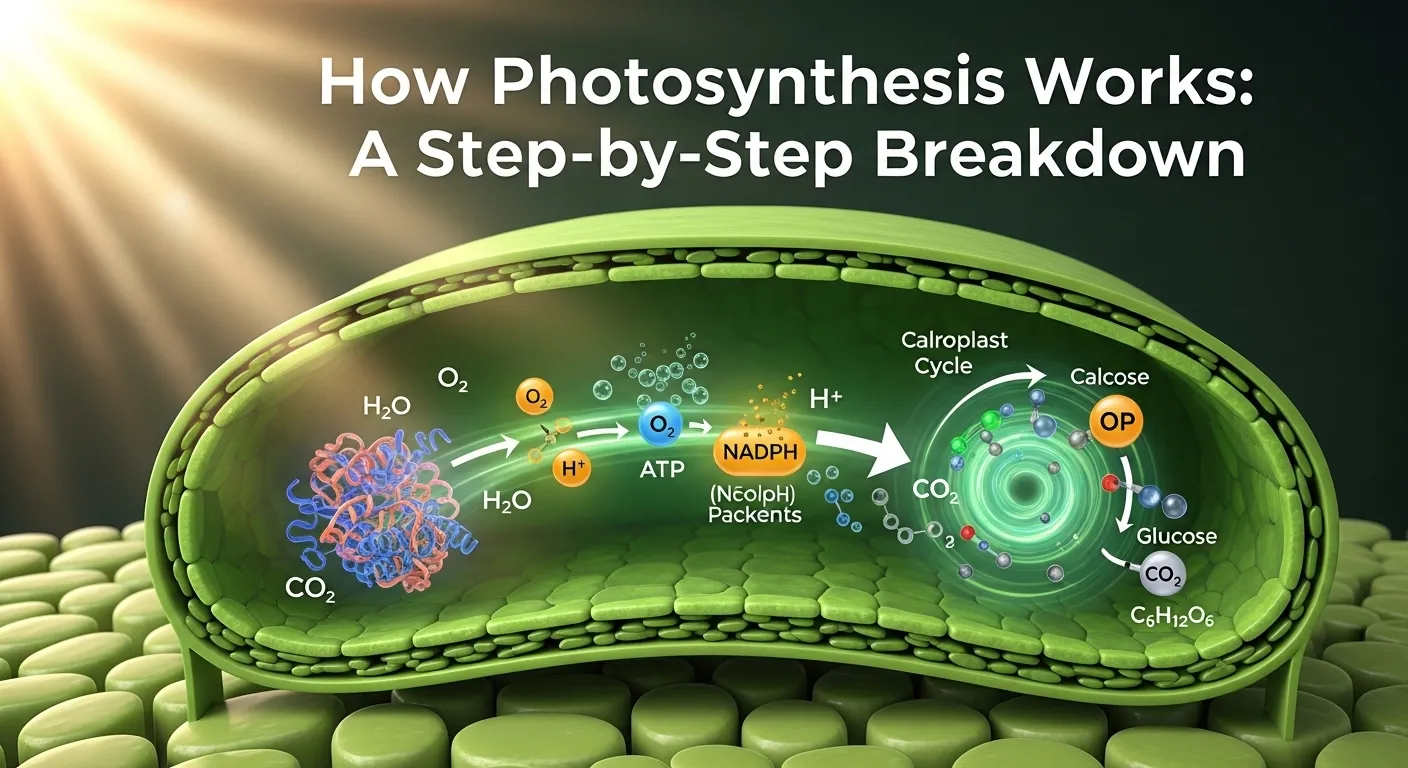

Life on Earth is a vibrant tapestry of interconnected systems, but a single, silent process powers almost all of it: photosynthesis. This remarkable biological alchemy, performed by plants, algae, and some bacteria, converts simple sunlight into the chemical energy that fuels ecosystems, builds biomass, and produces the very air we breathe. It's a process so fundamental that without it, the world as we know it would cease to exist. But how does this solar-powered engine for life actually function? To truly appreciate this marvel, we need to understand how does photosynthesis work step by step, from the first photon of light striking a leaf to the final creation of a sugar molecule. This article will serve as your comprehensive guide, breaking down this complex process into understandable stages. We will journey inside the microscopic world of the plant cell, explore the two major acts of this biochemical drama, and uncover the critical factors that can influence its efficiency. Prepare to demystify the magic that happens in every green leaf around you. What is Photosynthesis? The Foundation of Life on Earth At its core, photosynthesis is the process used by photoautotrophs—organisms that make their own food using light—to convert light energy into chemical energy. This chemical energy is then stored in the bonds of carbohydrate molecules, such as glucose (sugar), which the organism can use for fuel. The overall process can be summarized by a deceptively simple chemical equation: 6CO₂ + 6H₂O + Light Energy → C₆H₁₂O₆ + 6O₂. This tells us that six molecules of carbon dioxide and six molecules of water, in the presence of light, produce one molecule of glucose and six molecules of oxygen. The importance of this conversion cannot be overstated. The glucose produced is the primary source of energy for the plant itself, fueling its growth, reproduction, and all other metabolic activities. When animals eat plants (or eat animals that have eaten plants), they are essentially transferring this stored solar energy into their own bodies. This makes photosynthesis the ultimate source of energy for nearly every food chain on the planet. Furthermore, the oxygen released as a byproduct is crucial for aerobic respiration, the process most organisms, including humans, use to unlock energy from food. To pull off this incredible feat, plants require three key ingredients, often called reactants. The first is light energy, typically from the sun, which acts as the catalyst for the entire reaction. The second is carbon dioxide (CO₂) , a gas that plants absorb from the atmosphere through tiny pores on their leaves called stomata. The third ingredient is water (H₂O), which is primarily absorbed from the soil through the plant's roots. From these simple, inorganic inputs, the plant's internal machinery masterfully constructs complex organic molecules, with glucose and oxygen being the life-sustaining outputs, or products. The Photosynthetic Powerhouse: Inside the Chloroplast To understand where the magic of photosynthesis happens, we must zoom in from the whole plant to a single leaf, then to a single cell, and finally, to a specialized organelle within that cell: the chloroplast. These tiny, oval-shaped structures are the dedicated factories for photosynthesis in plant and algal cells. A typical plant cell in a leaf can contain dozens or even hundreds of chloroplasts, each working tirelessly to convert sunlight into usable energy. The green color we associate with plants is due to the pigment chlorophyll, which is densely packed within these chloroplasts and is essential for capturing light. The structure of the chloroplast is perfectly designed for its function, featuring a complex system of internal membranes. It is enclosed by a double membrane—an outer and an inner membrane—that regulates the passage of materials in and out. The fluid-filled space within the inner membrane is called the stroma. It's a dense, enzyme-rich soup where the second major stage of photosynthesis occurs. Suspended within this stroma is a third membrane system, consisting of flattened, sac-like structures called thylakoids. These are the critical sites for the first stage of photosynthesis. Thylakoids are often arranged in stacks, much like a stack of coins, known as grana (singular: granum). The membrane of each thylakoid contains the chlorophyll molecules and other protein complexes that form the light-capturing machinery. The space inside a thylakoid is called the thylakoid lumen. This intricate arrangement of membranes and compartments—the stroma, the thylakoids, and the lumen—allows the plant to create chemical gradients and segregate the different stages of photosynthesis, maximizing efficiency and control over the entire process. The First Act: The Light-Dependent Reactions The first major phase of photosynthesis is aptly named the light-dependent reactions because, as the name suggests, it directly requires light to proceed. This stage is all about converting light energy into short-term chemical energy. Think of it as charging a battery. The primary location for this act is within the thylakoid membranes inside the chloroplasts. Here, the energy from photons of light is captured and used to create two vital energy-carrying molecules: ATP (adenosine triphosphate) and NADPH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate). Oxygen is also released as a crucial byproduct during this stage. These reactions are a rapid and elegant sequence of events involving multiple protein complexes and electron carriers embedded in the thylakoid membrane. The entire process is driven by the energy of sunlight, which excites electrons and initiates a flow of energy through a system known as an electron transport chain. Let's break down this first act into its key scenes. Light Absorption and Electron Excitation The process begins when a photon of light strikes a pigment molecule, primarily chlorophyll, located within large protein complexes called photosystems. There are two types of photosystems involved: Photosystem II (PSII) and Photosystem I (PSI), which, despite their names, work in sequence with PSII acting first. When chlorophyll absorbs light energy, it doesn't get hot; instead, the energy is used to boost one of its electrons to a higher, more energetic state. This "excited" electron is now unstable and ready to be passed along to another molecule. This transfer of energy is incredibly efficient.