Coral Reef Conservation Efforts That Actually Work

Of course. As an SEO expert, I will craft a comprehensive, unique, and engaging article on coral reef conservation that is optimized for search engines and provides long-term value.

Here is the article:

—

The vibrant, underwater cities we call coral reefs are facing an unprecedented crisis. These breathtaking ecosystems, teeming with a quarter of all marine life, are disappearing at an alarming rate due to climate change, pollution, and direct human pressures. Yet, amid the bleak headlines of widespread bleaching and ecosystem collapse, a wave of innovation, dedication, and science is turning the tide. The global community is realizing that passive hope is not a strategy. Instead, a suite of targeted and effective conservation efforts to protect coral reefs is demonstrating that recovery is possible. This article dives deep into the methods that aren't just theoretical but are actively being implemented and proving successful in the field, offering a blueprint for hope and a call to action for our planet's most vital marine habitats.

The Bedrock of Protection: Establishing and Enforcing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

At the forefront of large-scale coral reef conservation lies the concept of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). These are essentially national parks for the ocean, designated zones where human activities are restricted to protect the natural environment. While the idea is simple, its effective implementation is a powerful tool for allowing reefs to recover from stress. By limiting or outright banning destructive practices like overfishing, bottom trawling, and unregulated tourism, MPAs provide a sanctuary where marine ecosystems can regain their balance and resilience.

The success of an MPA hinges on more than just drawing lines on a map. Effective management and strict enforcement are non-negotiable. This includes regular patrols to prevent illegal fishing, the installation of mooring buoys to stop anchors from destroying fragile coral structures, and continuous scientific monitoring to assess the health of the reef. When well-managed, MPAs act as a buffer against direct, localized threats, giving corals a fighting chance to cope with larger, global stressors like rising sea temperatures. They become reservoirs of biodiversity, helping to replenish fish stocks and coral larvae in surrounding, unprotected areas.

Furthermore, community involvement is the secret ingredient that transforms a 'paper park' into a thriving sanctuary. When local communities, especially those who depend on the reef for their livelihoods, are included in the planning and management process, the likelihood of success skyrockets. They become the reef's primary guardians, possessing invaluable traditional knowledge and a vested interest in its long-term health. This collaborative approach ensures that conservation goals align with local economic and cultural needs, creating a sustainable model that benefits both people and nature.

The Power of 'No-Take' Zones

Within the broader category of MPAs, the most stringent and often most effective designation is the 'no-take' marine reserve. In these zones, all forms of extraction—including fishing, shelling, and even scientific collection without a permit—are prohibited. The results can be dramatic and surprisingly swift. Freed from the constant pressure of fishing, populations of key herbivorous fish, such as parrotfish and surgeonfish, can rebound.

These herbivores play a critical role in reef health by grazing on algae, which would otherwise overgrow and smother corals, especially after a bleaching event. A healthy fish population keeps algae in check, clearing space for new coral larvae to settle and grow. The famous Apo Island Marine Sanctuary in the Philippines is a textbook example. After the establishment of a small no-take zone, fish biomass increased dramatically, an effect that 'spilled over' into adjacent fishing grounds, ultimately increasing the catch for local fishers and proving that conservation can directly support livelihoods.

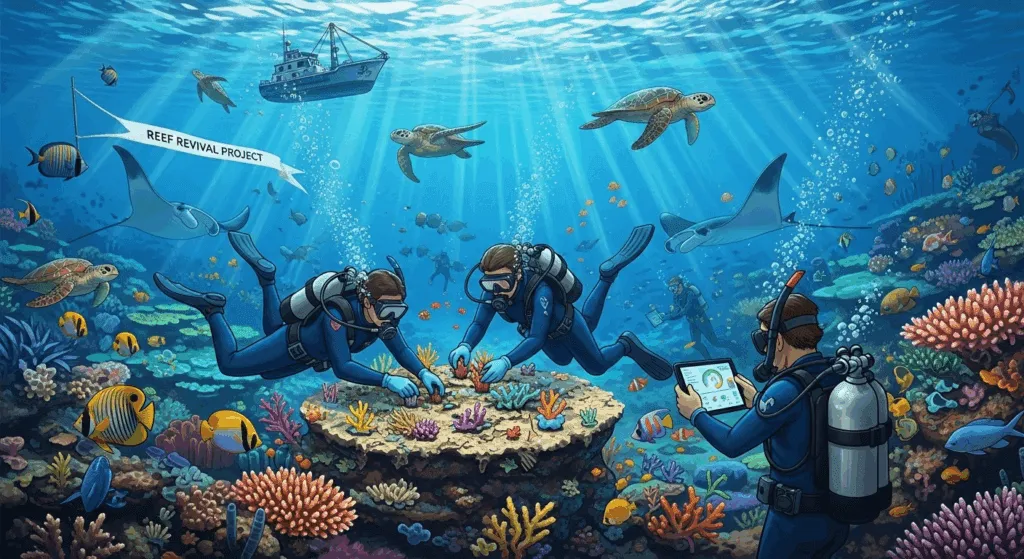

Active Intervention: The Science of Coral Restoration and Gardening

While MPAs protect healthy or recovering reefs, what about areas that are already severely degraded? This is where active restoration comes into play. Coral gardening, a technique analogous to terrestrial forestry, has emerged as a leading method for kick-starting recovery. It involves collecting small fragments of surviving corals, growing them in controlled underwater or land-based nurseries, and then 'outplanting' them back onto degraded reefs. This process gives young corals a head start in a safe environment, away from predators and sediment, before they are strong enough to survive on the reef.

The 'gardens' themselves can take many forms, from underwater 'coral trees' where fragments are hung from PVC pipes to simple tables on the seafloor. This method allows restoration practitioners to grow thousands of corals at a time. It's particularly effective for fast-growing branching species like staghorn (Acropora cervicornis) and elkhorn (Acropora palmata), which have suffered massive declines in the Caribbean. By focusing on these framework-building species, restoration projects can rapidly rebuild the complex three-dimensional structure of the reef, which is essential for attracting fish and other marine life.

However, a crucial lesson learned has been the importance of genetic diversity. Early projects sometimes relied on fragments from a single, resilient colony. But a "super coral" in one location might be vulnerable to a new disease or different stressor. Therefore, modern restoration prioritizes collecting fragments from many different parent colonies to create a genetically diverse "portfolio" of outplanted corals. This increases the overall resilience of the restored reef, giving it a better chance of adapting to future environmental changes.

A Game-Changer: Microfragmentation

One of the most significant breakthroughs in coral restoration is a technique called microfragmentation, pioneered by Dr. David Vaughan at the Mote Marine Laboratory. The discovery was serendipitous: when a small piece of coral broke off by accident, it began to grow back at a much faster rate than the larger colony. This led to the realization that if you cut a mound-forming coral (like brain or star corals) into tiny, one-centimeter fragments, you can trigger their natural healing and growth mechanisms.

These microfragments can grow 25 to 50 times faster than they would in the wild. But the magic doesn't stop there. When fragments from the same parent colony are placed next to each other on the reef, they recognize their shared genetics and fuse together. This allows practitioners to create a large, boulder-sized coral colony in just one or two years, a process that would naturally take decades or even centuries. This not only accelerates the rebuilding of reef structure but also helps the corals reach sexual maturity much faster, enabling them to reproduce and seed the reef on their own.

Tackling Threats at the Source: Pollution and Runoff Management

Coral reefs don't exist in a vacuum. They are intricately connected to the land, and what happens upstream inevitably affects them. Land-based pollution is a major driver of reef degradation, but it's also one of the threats that local and regional governments have the most power to control. Tackling these local stressors is a critical part of a holistic conservation strategy because it boosts the reef's overall health, making it more resilient to the global threat of climate change.

The three main culprits of land-based pollution are sediment, nutrients, and chemicals. Sediment runoff from coastal development, deforestation, and poor agricultural practices can cloud the water, cutting off the sunlight that corals' symbiotic algae need to photosynthesize. In severe cases, sediment can directly smother and kill corals. Nutrient runoff, primarily from fertilizers and sewage, fuels the explosive growth of macroalgae that outcompetes corals for space and light, disrupting the entire ecosystem balance.

Effective management requires an integrated "ridge-to-reef" approach. This involves improving wastewater treatment facilities to reduce nutrient loads, promoting agricultural best practices like planting vegetation buffers along waterways to trap sediment and fertilizer, and implementing stricter regulations on coastal construction. Restoring coastal habitats like mangroves and seagrass beds also plays a vital role, as these ecosystems act as natural filters, trapping pollutants before they reach the delicate coral reefs.

| Type of Pollutant | Primary Sources | Direct Impact on Coral Reefs |

|---|---|---|

| Sediment | Coastal Development, Deforestation, Agriculture | Reduces water clarity (less sunlight for photosynthesis), can directly smother and kill corals. |

| Nutrients (Nitrogen, Phosphorus) | Sewage Outflow, Agricultural Fertilizers | Fuels algal blooms that outcompete corals for space and light, leading to ecosystem imbalance. |

| Chemicals & Toxins | Pesticides, Industrial Waste, Sunscreen (Oxybenzone, Octinoxate) | Can cause coral bleaching, impair reproduction, and lead to deformities in coral larvae. |

| Plastics & Debris | Mismanaged Waste, Stormwater Runoff | Can physically smother and break corals; microplastics can be ingested, causing internal damage. |

The Human Element: Community-Led Conservation and Sustainable Tourism

Top-down conservation efforts often face challenges with enforcement and local acceptance. A more enduring and equitable model is community-led conservation, which empowers the people who live closest to the reefs to become their primary stewards. This approach recognizes that local communities possess deep, generational knowledge of their marine environments and have the most to lose from their degradation.

Programs that successfully integrate communities often focus on co-management, where responsibility for monitoring and enforcing rules is shared between government agencies and local user groups. This can involve training local fishers as "reef rangers" to monitor for illegal activities and track ecosystem health. Crucially, these programs must also provide tangible benefits to the community. This often means developing alternative, sustainable livelihoods that reduce direct pressure on the reef, such as seaweed farming, handicraft production, or, most significantly, sustainable tourism.

Sustainable tourism, when managed correctly, can be a powerful engine for conservation. It transforms a healthy reef from a simple resource to be extracted into a valuable, living economic asset. This model incentivizes the entire community to protect the reef because their income depends on it.

Transforming Tourism from a Threat to an Ally

Unregulated tourism can be incredibly destructive, with divers and snorkelers breaking fragile corals, boats dropping anchors indiscriminately, and chemical-laden sunscreens washing off into the water. However, a sustainable model flips this paradigm. Best practices include the mandatory use of mooring buoys, establishing clear "no-touch" policies for all visitors, and limiting the number of people allowed on a reef at any given time to reduce pressure.

Many successful sustainable tourism operations also incorporate a strong educational component, teaching visitors about coral biology and the threats they face. Furthermore, the implementation of "user fees" or "eco-taxes" for tourists can generate a dedicated stream of funding that goes directly back into conservation management, such as paying for patrols, restoration projects, and scientific monitoring. The nation of Palau is a global leader in this, having implemented the "Palau Pledge", where visitors must sign a passport stamp pledging to act in an environmentally responsible way for the sake of Palau's children.

The Frontier of Hope: Assisted Evolution and Genetic Intervention

Even with the best management practices, the sheer speed and scale of climate change present an existential threat. Ocean temperatures are rising faster than many coral species can naturally adapt. This has pushed scientists to explore more radical, high-tech interventions collectively known as "assisted evolution." This is a proactive approach that aims to accelerate corals' natural adaptive processes to help them survive in the warmer, more acidic oceans of the future.

This field of research is exploring several promising avenues. One involves stress-hardening, where corals are exposed to sub-lethal levels of heat in nurseries to improve their thermal tolerance before being outplanted. Another focuses on the corals' symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae). Scientists are actively isolating and culturing more heat-tolerant strains of these algae and introducing them to corals, essentially giving them a supercharged, more resilient "power pack."

While these techniques are still largely in the experimental stage, they hold enormous potential. More advanced research is even delving into selective breeding—cross-breeding naturally resilient coral colonies to create offspring with enhanced thermal tolerance—and even cryopreservation. Just as we have "seed vaults" for terrestrial plants, scientists are now creating frozen biobanks of coral sperm, eggs, and embryos. This serves as a critical genetic insurance policy, preserving the biodiversity of today's reefs for potential reintroduction in a future where conditions may be more favorable. These efforts are controversial and carry risks, but many scientists argue they are necessary in the face of an unprecedented global crisis.

—

Conclusion

The fight to save the world's coral reefs is one of the defining conservation challenges of our time. It is a battle waged on multiple fronts, from global climate policy to the microscopic genetics of a single coral polyp. There is no single magic bullet. The conservation efforts that actually work are those that are integrated, adaptive, and collaborative.

Success lies in a multi-layered strategy: protecting large, intact reefs with well-managed MPAs; actively rebuilding degraded areas through innovative restoration techniques like microfragmentation; staunching the flow of land-based pollution at its source; empowering local communities to become reef guardians through sustainable livelihoods; and bravely exploring the cutting edge of science with assisted evolution. Each effort reinforces the others, building ecosystem resilience from the ground up. While the road ahead is long and the threat of climate change looms large, these proven strategies demonstrate that with sufficient will, investment, and ingenuity, we can give our planet's underwater cities a fighting chance at survival and recovery.

—

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What is the single most effective way to protect coral reefs?

A: The single most impactful action is to combat global climate change by drastically reducing greenhouse gas emissions, as rising ocean temperatures and acidification are the primary threats. On a local and regional level, establishing and properly enforcing large 'no-take' Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) is widely considered the most effective foundational strategy for allowing reefs to recover and thrive.

Q: Can coral reefs fully recover from a bleaching event?

A: Yes, they can, but it depends on the severity and duration of the heat stress. Coral bleaching is the expulsion of the symbiotic algae that live in the coral's tissue. If the water temperature returns to normal within a few weeks, the algae can return and the coral can recover. However, if the stress is prolonged, the coral will starve and die. Recovery is also more likely on reefs that are not facing other stressors like pollution or overfishing.

Q: As a tourist, what can I do to help protect coral reefs?

A: You can make a significant difference. First, choose "reef-safe" sunscreen that does not contain oxybenzone and octinoxate. Second, practice responsible snorkeling and diving: never touch, stand on, or kick the coral. Third, choose tour operators who are committed to sustainability (e.g., they use mooring buoys instead of anchors). Finally, pay any park or user fees happily, as this money often directly funds conservation work.

Q: What is the difference between coral conservation and coral restoration?

A: Think of it like this: Conservation is about protecting what you already have. It involves strategies like creating MPAs, reducing pollution, and managing fishing to prevent damage to existing, healthy reefs. Restoration is about actively rebuilding what has been lost. It involves techniques like coral gardening and microfragmentation to grow corals and outplant them onto degraded reefs to kick-start the recovery process. Both are essential components of a complete strategy.

—

Summary

This article explores the diverse and effective conservation efforts to protect coral reefs that are currently being implemented worldwide. It moves beyond theoretical concepts to focus on methods with proven success. The core strategies discussed include the establishment of well-managed Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), particularly 'no-take' zones, which serve as a foundation for ecosystem recovery by eliminating direct human pressures like overfishing.

The article then delves into active restoration techniques, highlighting the evolution of coral gardening and a groundbreaking method known as microfragmentation, which can accelerate coral growth by up to 50 times. It also emphasizes the critical importance of tackling land-based pollution through "ridge-to-reef" management to improve water quality and boost reef resilience. Furthermore, the role of community-led conservation and the development of sustainable tourism are presented as vital for long-term success, turning local populations into the reef's most dedicated guardians. Finally, it looks to the future, examining cutting-edge scientific interventions like assisted evolution and the creation of coral biobanks, which aim to help corals adapt to the unavoidable impacts of climate change. The overarching message is that a multi-pronged, integrated approach—combining protection, restoration, pollution control, community engagement, and science—offers the most viable path forward for saving these critical ecosystems.