How Do Carnivorous Plants Trap Their Prey? An Inside Look

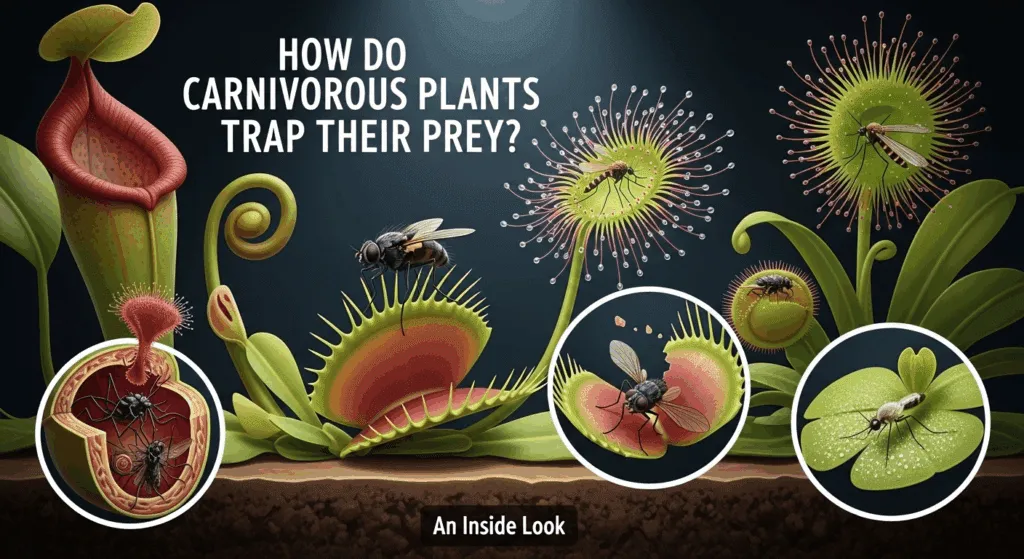

In the vast and strange kingdom of plants, a select few have defied the norms of their kind. While most plants passively draw nutrients from the soil and sun, these botanical predators have evolved to hunt, trap, and consume living creatures. They are the carnivorous plants, masters of adaptation living in some of the world's most nutrient-poor environments. The image of a Venus flytrap snapping shut on an unsuspecting fly is iconic, but it only scratches the surface of their sophisticated hunting prowess. The central question that fascinates botanists and nature lovers alike is, how do carnivorous plants trap their prey with such lethal precision and diversity? This inside look will journey into the intricate and often startling world of their trapping mechanisms.

How Do Carnivorous Plants Trap Their Prey? An Inside Look

The Fundamental Need: Why Plants Became Predators

Before diving into the "how," it's crucial to understand the "why." Carnivorous plants didn't evolve to be predatory out of malice; they did it out of necessity. These remarkable species typically grow in environments like bogs, fens, and waterlogged soils where essential nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus, are scarce. While they still perform photosynthesis to create energy from sunlight, the soil simply doesn't provide the building blocks they need for proteins, DNA, and other vital molecules.

To solve this nutritional deficit, they developed an extraordinary adaptation: carnivory. By capturing and digesting small animals—mostly insects and other arthropods—they supplement their diet, extracting the necessary nitrogen and phosphorus from their prey's bodies. This ability gives them a significant competitive advantage in these harsh habitats, allowing them to thrive where other plants would struggle or perish. It's a perfect example of evolutionary pressure leading to a highly specialized and fascinating survival strategy.

This predatory lifestyle is a delicate balancing act. Creating and maintaining complex traps, producing nectar lures, and secreting digestive enzymes all require a significant energy investment. Therefore, for a carnivorous plant, the nutritional benefit gained from capturing prey must outweigh the energetic cost of the hunt. This cost-benefit analysis has driven the evolution of incredibly efficient and diverse trapping mechanisms, each fine-tuned to its environment and preferred prey.

An Arsenal of Deception: The Five Main Trapping Mechanisms

The world of carnivorous plants is a showcase of evolutionary ingenuity, with over 600 species employing a variety of trapping strategies. While there are countless variations, these methods can be broadly categorized into five fundamental types. Some are passive, relying on their static structure to lure and ensnare victims, while others are active, using rapid movement to catch their prey by surprise. Understanding these five core strategies is key to appreciating the full spectrum of their predatory abilities.

These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive in their features; many plants combine elements, such as using adhesive surfaces within a pitfall trap. However, each species typically relies on one primary strategy. The five main trapping mechanisms are:

- Pitfall Traps: Luring prey into a cavity from which it cannot escape.

- Flypaper (Adhesive) Traps: Using sticky mucilage to ensnare insects.

- Snap Traps (Steel Traps): Employing rapid leaf movement to enclose prey.

- Suction Traps (Bladder Traps): Sucking prey into a bladder with a vacuum.

- Lobster-Pot Traps: Forcing prey to move towards a digestive organ through a one-way path.

The following table provides a quick comparison of these fascinating strategies:

| Trapping Mechanism | Trap Type | Example Plant(s) | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pitfall Trap | Passive | Pitcher Plants (Nepenthes, Sarracenia) | A deep cavity filled with digestive fluid, often with a slippery rim. |

| Flypaper Trap | Passive/Active | Sundews (Drosera), Butterworts (Pinguicula) | Glands that secrete sticky mucilage to trap and suffocate prey. |

| Snap Trap | Active | Venus Flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) | Hinged leaf lobes that snap shut in a fraction of a second. |

| Suction Trap | Active | Bladderworts (Utricularia) | A small bladder that uses a vacuum to suck in small aquatic prey. |

| Lobster-Pot Trap | Passive | Corkscrew Plant (Genlisea) | Underground Y-shaped leaves that guide soil organisms into a digestive chamber. |

Active Traps: The Art of Rapid Movement

Active traps are perhaps the most dramatic, as they involve visible, rapid movement to secure a meal. These mechanisms are energy-intensive but incredibly effective, representing a pinnacle of plant mechanics and sensitivity. They rely on complex biophysical processes to achieve speeds that are almost unbelievable for a member of the plant kingdom.

The Snap Trap: A Botanical Bear Trap

The quintessential example of an active trap is the Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula). Its iconic trap consists of two hinged lobes, fringed with cilia that interlock like teeth when the trap closes. The inner surface of these lobes is dotted with tiny, highly sensitive trigger hairs. For the trap to spring, an insect must touch two different trigger hairs in quick succession or the same hair twice within about 20 seconds. This sophisticated triggering system prevents the plant from wasting energy on false alarms caused by raindrops or falling debris.

When the trigger hairs are stimulated, they generate a tiny electrical signal that travels across the leaf lobes. This signal instigates a rapid change in the water pressure within the cells of the leaf's midline—a process known as a change in turgor pressure. The outer cells of the lobes expand quickly while the inner cells contract, causing the leaf's shape to flip from convex (curved outward) to concave (curved inward). This action snaps the lobes shut in as little as 100 milliseconds, a speed too fast for most insects to escape. Once closed, the struggling insect continues to stimulate the hairs, prompting the trap to seal completely and begin releasing digestive enzymes.

The Suction Trap: The Fastest Predator on Earth

While the Venus flytrap is famous, the title of the fastest hunter in the plant world belongs to the Bladderwort (Utricularia). These mostly aquatic or soil-dwelling plants have hundreds of tiny, pear-shaped bladders, each a highly complex suction trap. The bladder is held under negative pressure—a partial vacuum is created by pumping water out. At the front of the bladder is a small trapdoor sealed shut and surrounded by trigger hairs.

When a tiny aquatic creature, like a water flea or a mosquito larva, brushes against these trigger hairs, the trapdoor is released. The vacuum inside the bladder is instantly equalized, sucking the unsuspecting prey and the surrounding water into the bladder. This entire process occurs in under a millisecond, making it one of the fastest known movements in the biological world. Once inside, the trapdoor seals again, the plant pumps the water back out to reset the vacuum, and digestion of the captured organism begins. The sheer speed and mechanical elegance of the bladderwort's trap are a marvel of natural engineering.

Passive Traps: A Patient and Deadly Game

Unlike their active counterparts, passive traps don't rely on movement to capture their prey. Instead, they have evolved intricate structures that function as natural, self-operating prisons. They use a combination of alluring scents, vibrant colors, and clever architectural features to lure victims to their doom. These methods are highly energy-efficient, as the trap is always "set."

The Pitfall Trap: The Pit of No Return

Pitfall traps are most famously employed by Pitcher Plants. These plants, which include genera like Nepenthes (tropical pitcher plants) and Sarracenia (North American pitcher plants), have modified leaves that form a deep, hollow pitcher filled with a pool of liquid. This is not just rainwater; it's a "soup" of digestive enzymes and wetting agents secreted by the plant. The plant lures insects with a combination of bright colors, ultraviolet patterns visible only to insects, and a trail of sweet nectar leading up the outside of the pitcher.

The trap's effectiveness lies in its treacherous rim, known as the peristome. This surface is often incredibly slippery, especially when wet, due to a microscopic structure that prevents insect footpads from getting a grip. Nectar is also secreted here, encouraging the insect to venture onto this perilous edge. One small slip sends the prey tumbling into the fluid below. To make escape even more difficult, the inner walls of the pitcher are often coated with a waxy substance or lined with sharp, downward-pointing hairs, ensuring that any attempt to climb out is futile. The exhausted prey eventually drowns and is slowly broken down by the digestive enzymes.

The Flypaper Trap: A Sticky Situation

The flypaper or adhesive trap is a simple yet brilliant strategy used by plants like the Sundew (Drosera) and the Butterwort (Pinguicula). These plants have leaves covered in glands that secrete a sticky, glistening substance called mucilage. To a thirsty or hungry insect, these droplets look like sweet nectar or dew, a tempting offer that quickly turns deadly.

Sundews are covered in tentacles, each tipped with a globe of this mucilage. When an insect lands on a leaf, it becomes stuck. Its struggles to escape only bring it into contact with more sticky tentacles. In many species of Drosera, this struggle triggers movement—the tentacles and sometimes the entire leaf will slowly curl around the prey, a process called thigmotropism. This action maximizes contact between the insect and the digestive glands, ensuring efficient digestion and nutrient absorption. Butterworts, on the other hand, have broad, greasy-feeling leaves with a flat surface covered in two types of glands: stalked glands to trap the prey and sessile glands to digest it.

The Underworld of Traps: Digestion and Nutrient Absorption

Capturing prey is only the first half of the battle. Once an organism is trapped, the plant must break it down and absorb its nutrients. This process is a form of external digestion, strikingly similar to what happens in an animal's stomach, but it occurs on the surface or within the cavity of a modified leaf. This is where the true chemical warfare begins.

The Digestive Cocktail

Upon securing its prey, the carnivorous plant secretes a potent cocktail of digestive enzymes. The specific enzymes vary between species but often include:

- Proteases: Break down proteins into amino acids.

- Chitinases: Break down chitin, the hard exoskeleton of insects.

- Phosphatases: Release phosphate from organic molecules.

- Nucleases: Break down DNA and RNA into their constituent parts.

In many pitcher plants, the digestive fluid is also highly acidic, which helps to kill the prey and inhibit bacterial growth, ensuring the plant gets the full nutritional benefit without competition from microbes. In some cases, plants form a symbiotic relationship with bacteria or other organisms living within their traps, which help to break down the prey in a process known as mutualistic digestion.

Absorbing the Feast

Once the prey’s body has been reduced to a nutrient-rich soup, the plant begins the final and most important step: absorption. Specialized cells on the surface of the trap, similar to the root cells that absorb nutrients from the soil, actively transport the valuable molecules—especially nitrogen- and phosphorus-containing compounds—into the plant's tissues.

This absorbed "meal" is then distributed throughout the plant, fueling its growth, flowering, and seed production. The hard, indigestible parts of the prey, such as the outer exoskeleton, are often left behind in the trap. This entire process, from trapping to full absorption, can take anywhere from a few days to several weeks, depending on the size of the prey and the type of plant. It is this final step that fulfills the evolutionary purpose of carnivory: to obtain life-sustaining nutrients that are otherwise unavailable.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Can carnivorous plants eat humans or large animals?

A: Absolutely not. This is a common myth popularized by science fiction. The largest carnivorous plants, like some giant species of Nepenthes, are known to occasionally trap small vertebrates like frogs, lizards, or even small rodents, but their traps are nowhere near large or strong enough to capture a human or a large animal. Their primary diet consists of insects and other small arthropods.

Q: Do carnivorous plants still perform photosynthesis?

A: Yes, they do. Carnivory is a nutritional supplement, not a replacement for photosynthesis. All carnivorous plants are green and contain chlorophyll, allowing them to create their own energy from sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide, just like other plants. The "food" they catch provides essential minerals, not primary energy.

Q: How many species of carnivorous plants are there?

A: There are currently over 630 recognized species of carnivorous plants, with new ones still being discovered. They are found on every continent except Antarctica, in a wide variety of habitats, from tropical rainforests to chilly northern bogs.

Q: Can I grow a carnivorous plant at home?

A: Yes, many species, such as the Venus flytrap, certain pitcher plants (Sarracenia), and sundews (Drosera capensis), are popular houseplants. However, they have specific care requirements. They generally need high humidity, bright light, and nutrient-poor, mineral-free water (like distilled water or rainwater). Feeding them tap water or planting them in standard potting soil will kill them.

Conclusion: Nature's Ingenious Hunters

Carnivorous plants are a profound testament to the power of evolution to find creative solutions to life's challenges. Faced with starvation in nutrient-barren soils, they didn't just survive; they became hunters, developing an astonishing array of traps that are as beautiful as they are lethal. From the lightning-fast snap of the Venus flytrap and the vacuum-powered suction of the bladderwort to the patient, passive allure of pitcher plants and sundews, each mechanism is a masterclass in physics, chemistry, and biology.

By transforming their leaves from simple solar panels into complex machines of death and digestion, these plants have secured their place in some of the most unforgiving landscapes on Earth. They remind us that the natural world is filled with wonders that defy our expectations and that even the seemingly peaceful kingdom of plants has its share of sophisticated and successful predators.

***

Article Summary

This article, "How Do Carnivorous Plants Trap Their Prey? An Inside Look," provides a comprehensive exploration of the hunting mechanisms of carnivorous plants. It begins by explaining that these plants evolved carnivory as a necessary adaptation to thrive in nutrient-poor environments, using insects to supplement their intake of nitrogen and phosphorus.

The core of the article details the five primary trapping strategies:

- Pitfall Traps: Used by Pitcher Plants, which lure prey into a deep cavity of digestive fluid with a slippery rim.

- Flypaper Traps: Employed by Sundews and Butterworts, which use sticky mucilage to ensnare insects.

- Snap Traps: The famous mechanism of the Venus Flytrap, which uses rapid leaf movement triggered by sensitive hairs to enclose prey.

- Suction Traps: The incredibly fast method of Bladderworts, which use a vacuum to suck prey into a small bladder.

- Lobster-Pot Traps: A one-way system used by plants like the Corkscrew Plant to guide prey towards a digestive chamber.

The article further examines what happens after a successful capture, detailing the process of digestion and absorption. Plants secrete a cocktail of enzymes (like proteases and chitinases) to break down the prey into a nutrient-rich liquid, which is then absorbed by specialized cells. Finally, a FAQ section addresses common questions about these plants, such as their diet, their reliance on photosynthesis, and tips for home cultivation. The article concludes by positioning carnivorous plants as marvels of evolutionary adaptation.