The Function of Xylem and Phloemin Plants Explained

Of course. As an SEO expert, I will create a comprehensive, unique, and engaging article on the function of xylem and phloem that is optimized for search engines and provides long-term value.

Here is the article:

—

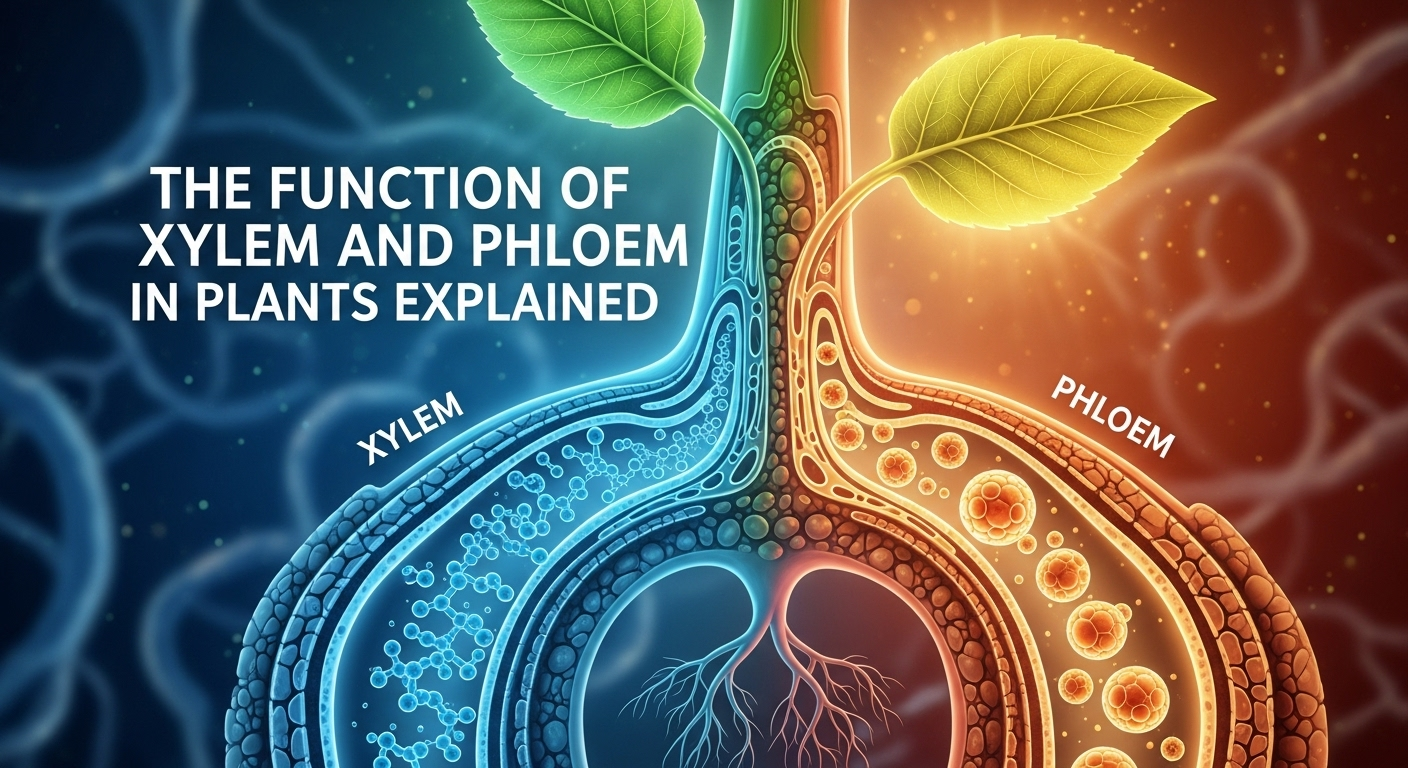

Have you ever wondered how a towering redwood tree gets water from its deep roots all the way to its highest leaves, or how the sweet energy produced in a leaf during a sunny afternoon nourishes the fruit on a distant branch? Plants, much like animals, have a sophisticated internal transport system that makes these incredible feats possible. This intricate network is the plant's vascular system, a lifeline composed of two critical tissues. Understanding what is the function of xylem and phloem in plants is the key to unlocking the secrets of their survival, growth, and remarkable efficiency. These two components work in a beautifully coordinated partnership, ensuring every part of the plant receives the water, minerals, and energy it needs to thrive.

The Function of Xylem and Phloem in Plants Explained

The Vascular System: The Lifeline of a Plant

At the heart of a plant's anatomy lies its vascular system, a complex network of conductive tissues that functions as its circulatory system. This system is the plant's internal plumbing, responsible for transporting vital substances over what can be incredible distances—from the finest root hair buried in the soil to the topmost bud reaching for the sun. Without this system, plants would be unable to grow beyond a very small size, as simple diffusion would be insufficient to meet their metabolic needs. The evolution of this efficient transport network was a pivotal moment in the history of life on Earth, allowing plants to conquer land and achieve the massive sizes we see today.

This essential system is organized into structures called vascular bundles, which contain both xylem and phloem tissues running side-by-side. You can see these bundles in the veins of a leaf, arranged in a ring within a stem, or clustered in the central core of a root. Their arrangement differs between plant groups (like monocots and dicots), but their fundamental purpose remains the same: to act as a two-way highway for resources. The xylem forms the upward-bound lane, while the phloem constitutes the multidirectional network for nutrient distribution, ensuring a constant and reliable supply chain throughout the organism.

The importance of the vascular system cannot be overstated. It directly supports photosynthesis by delivering water to the leaves, provides the building blocks for new growth by distributing sugars, and offers structural rigidity that helps plants stand upright against gravity. It's a dynamic system that responds to the plant's changing needs, whether it's channeling more water on a hot day or sending extra energy to developing fruits and seeds. By understanding the distinct roles of its two main components, xylem and phloem, we can appreciate the elegant engineering that underpins all plant life.

Deep Dive into Xylem: The Water Superhighway

The primary and most well-known function of the xylem is the bulk transport of water and dissolved minerals from the roots to the rest of the plant. Imagine it as a sophisticated, one-way plumbing system. After water is absorbed by the roots from the soil, it enters the xylem and begins its upward journey through the stem and into the leaves, flowers, and fruits. This water is crucial for many processes, including acting as a key reactant in photosynthesis, maintaining cell turgor (which keeps the plant from wilting), and cooling the plant through evaporation.

While water transport is its main job, xylem also plays a vital secondary role: providing structural support. The cells that make up the xylem have thick, rigid walls reinforced with a complex polymer called lignin. This lignification makes the xylem tissue incredibly strong and woody. In fact, what we know as "wood" in trees is almost entirely composed of accumulated xylem. This structural reinforcement helps plants stand tall, resist the forces of wind and gravity, and effectively position their leaves to capture maximum sunlight for photosynthesis.

The flow within the xylem is almost exclusively unidirectional, moving from the roots upwards to the shoots. This upward movement is primarily a passive process, meaning the plant does not expend metabolic energy to "pump" the water. Instead, it is driven by physical forces, primarily a phenomenon known as the transpiration pull. This efficient, energy-saving mechanism allows even the tallest trees to move hundreds of liters of water per day from the ground to their canopy, a truly remarkable feat of natural engineering.

The Cellular Structure of Xylem

Xylem is a complex tissue, meaning it is composed of several different types of cells. The main conducting cells, however, share a unique and fascinating characteristic: they are dead at maturity. When these cells are fully formed, their internal contents—the cytoplasm, nucleus, and vacuole—disintegrate, leaving behind a hollow, continuous tube. This "empty" structure is perfectly designed for its function, as it minimizes obstruction and allows water to flow through with minimal resistance. The thick, lignified cell walls left behind are what provide the structural support.

The two primary types of water-conducting cells in the xylem are tracheids and vessel elements.

- Tracheids are elongated, spindle-shaped cells that are found in all vascular plants, from ferns to conifers and flowering plants. They have tapered ends that overlap, and water moves from one tracheid to the next through small pits in their ajoining walls.

- Vessel elements are shorter, wider cells that are characteristic of angiosperms (flowering plants). They are stacked end-to-end to form a continuous tube called a vessel. The end walls between vessel elements have perforations or are completely absent, creating an open pipeline that is even more efficient at water transport than tracheids. This evolutionary innovation is one of the reasons for the widespread success of flowering plants.

The Mechanism of Water Transport in Xylem

The movement of water up the xylem is best explained by the Cohesion-Tension Theory. This model relies on the unique physical properties of water and the structure of the plant. The entire process begins in the leaves, where water evaporates into the atmosphere through tiny pores called stomata. This evaporation, known as transpiration, creates a negative pressure potential, or tension, in the xylem of the leaf. It’s like sipping water through a straw; the act of sipping creates negative pressure that pulls the liquid up.

This tension pulls on the entire column of water in the xylem. This is possible because of two properties of water: cohesion and adhesion.

- Cohesion: Water molecules have a strong tendency to stick to each other due to hydrogen bonds. This creates an unbroken chain of water molecules extending all the way from the leaves down to the roots.

- Adhesion: Water molecules also stick to the lignified walls of the xylem cells. This adhesion helps to counteract the downward pull of gravity and prevents the water column from breaking.

Together, transpiration, cohesion, and adhesion create a continuous "transpiration stream" that passively pulls water up from the roots to the highest parts of the plant.

Understanding Phloem: The Nutrient Delivery Network

If xylem is the water pipe, then phloem is the food delivery service. The primary function of the phloem is to transport the sugars—mainly sucrose—produced during photosynthesis from the leaves to all other parts of the plant that need energy. This process is called translocation. The areas where sugars are produced (primarily mature leaves) are called sources, and the areas where sugars are used or stored (like roots, growing tips, flowers, and fruits) are called sinks. The phloem ensures that these energy-rich compounds are distributed according to the plant's needs.

Unlike the one-way street of the xylem, the flow in the phloem is bidirectional. This means the sugary sap can move both up and down the plant. For example, in the spring, a deciduous tree might move stored sugars up from its roots (a source) to new, developing leaves (a sink). Later in the summer, once those leaves are mature, they become the source, sending sugars down to the roots for storage. This flexible, demand-driven system allows the plant to allocate its energy resources with incredible precision and efficiency, supporting growth, reproduction, and defense.

While sugar is its main cargo, phloem is much more than just a sugar conduit. It is also a critical information highway. The sap flowing through the phloem carries a diverse array of other molecules, including amino acids, lipids, plant hormones, and signaling molecules like proteins and RNA. This complex mixture allows for communication between different parts of the plant, coordinating developmental processes, responses to environmental stress, and defense against pathogens. The phloem is truly the plant's central nervous system and nutrient network rolled into one.

The Living Cells of Phloem

A key difference between xylem and phloem is the nature of their conducting cells. While xylem conductors are dead at maturity, the cells of the phloem are alive and metabolically active. This is essential because the process of loading and unloading sugars is an active process that requires energy (ATP). Phloem is also a complex tissue, but its two most important components for translocation are the sieve-tube elements and their associated companion cells.

The sieve-tube elements (or sieve-tube members) are the main conducting cells. Like xylem vessel elements, they are arranged end-to-end to form a continuous tube, known as a sieve tube. To maximize space for transport, mature sieve-tube elements are highly modified. They lack a nucleus, vacuole, and ribosomes. Their end walls, called sieve plates, are perforated with pores that allow the sap to flow between cells. The companion cells are intimately linked to the sieve-tube elements via plasmodesmata (small channels). Each companion cell is responsible for the metabolic needs of its adjacent sieve-tube element. The companion cell contains a nucleus, ribosomes, and mitochondria, performing all the life-support functions and, crucially, providing the ATP needed to actively load sugars into the sieve tube.

The Pressure-Flow Hypothesis: How Phloem Works

The most widely accepted model for translocation in the phloem is the Pressure-Flow Hypothesis (or Munch hypothesis). This mechanism cleverly uses a pressure gradient generated by osmosis to drive the movement of sap. It begins at a source, such as a photosynthesizing leaf. Here, sugars (sucrose) are actively transported from the leaf cells into the companion cells and then loaded into the sieve-tube elements. This active loading requires energy from ATP.

As the concentration of sucrose increases inside the sieve tube, the water potential within the tube drops significantly. In response to this osmotic gradient, water moves from the adjacent xylem into the sieve tube via osmosis. This influx of water creates high turgor pressure, or hydrostatic pressure, at the source end of the sieve tube. This high pressure effectively pushes the sugary sap along the tube, much like how squeezing one end of a water balloon forces water to the other end.

The process concludes at a sink, such as the roots or a developing fruit. Here, the process happens in reverse. Sugar is actively unloaded from the sieve tube and moved into the sink cells for use or storage. As the sugar concentration in the sieve tube decreases, its water potential increases. Consequently, water moves out of the phloem and back into the xylem, reducing the hydrostatic pressure at the sink end. This difference in pressure between the source (high pressure) and the sink (low pressure) creates a continuous bulk flow of sap through the phloem.

Xylem vs. Phloem: A Comparative Analysis

While both xylem and phloem are the core components of a plant's vascular system, they are distinct in their structure, function, and mode of operation. Recognizing their differences is crucial to understanding the complete picture of plant physiology. Xylem is the structural, water-conducting backbone, operating passively through physical forces. In contrast, phloem is the living, dynamic network for nutrient and information distribution, driven by active, energy-dependent processes.

To summarize these key distinctions, the following table provides a clear, side-by-side comparison of the two vascular tissues:

| Feature | Xylem | Phloem |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Transport of water and dissolved minerals | Transport of sugars (translocation) |

| Direction of Flow | Unidirectional (upwards from roots to leaves) | Bidirectional (from source to sink, can be up or down) |

| Conducting Cells | Tracheids and Vessel Elements | Sieve-tube Elements |

| Cell State at Maturity | Dead, hollow, and lignified | Alive, but highly modified (lack nucleus) |

| Supporting Cells | Parenchyma and Fibers | Companion Cells, Parenchyma, and Fibers |

| Transport Mechanism | Passive (Cohesion-Tension Theory / Transpiration Pull) | Active (Pressure-Flow Hypothesis) |

| Secondary Function | Provides structural support (forms wood) | Information signaling (transports hormones, RNA) |

Despite their differences, xylem and phloem are not independent; they are deeply interconnected. The Pressure-Flow mechanism in the phloem relies entirely on water provided by the adjacent xylem to generate turgor pressure. Conversely, the living cells in the plant's roots, which are responsible for actively absorbing water and minerals for the xylem, are powered by the sugars delivered by the phloem. This symbiotic relationship highlights the integrated and codependent nature of the plant's vascular system, where one cannot function without the other.

The Importance of Vascular Tissues for Plant Health and Agriculture

A healthy, functioning vascular system is paramount for a healthy, productive plant. Any disruption to either the xylem or phloem can have severe consequences, leading to wilting, stunted growth, and even death. For example, prolonged drought can cause air bubbles (embolisms) to form in the xylem, breaking the cohesive water column and blocking water transport, which is why plants wilt and can eventually die during a water shortage. Understanding these functions is not just an academic exercise; it has immense practical applications.

Many plant diseases and pests specifically target the vascular system. Fungal diseases like Dutch elm disease and Verticillium wilt work by growing within the xylem vessels, physically clogging them and preventing water from reaching the leaves. Similarly, insects like aphids feed by piercing the phloem with their specialized mouthparts to steal the nutrient-rich sap, robbing the plant of its energy. A common horticultural practice called girdling, which involves removing a ring of bark (including the phloem) from a tree's trunk, will ultimately kill the tree because it severs the phloem's connection to the roots, starving them of the sugars they need to survive.

This knowledge is critical in agriculture and horticulture. Proper irrigation techniques are designed to ensure the xylem has a consistent supply of water. Fertilization strategies aim to provide the right minerals for the xylem to transport. Pruning methods can be used to manipulate an organism's source-sink relationships, for example, by removing some flower buds to encourage the plant to direct more sugar (via the phloem) to the remaining fruits, making them larger and sweeter. By understanding the intricate roles of xylem and phloem, we can better cultivate healthy crops, manage forests, and care for the plants in our homes and gardens.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What happens if the xylem in a plant is blocked?

A: If the xylem is blocked, the transport of water and minerals from the roots to the leaves will be interrupted. This leads to a rapid loss of turgor pressure in the leaves, causing them to wilt. The plant will also be unable to perform photosynthesis effectively, as water is a key ingredient. If the blockage is severe and widespread, the plant will eventually die from dehydration and starvation. This is the mechanism behind wilt diseases caused by certain fungi and bacteria.

Q2: Can phloem transport water?

A: While the primary liquid in phloem sap is water, the phloem's role is not bulk water transport in the same way as the xylem. The water in the phloem primarily acts as the solvent for sugars and other molecules and is essential for generating the pressure gradient described in the Pressure-Flow Hypothesis. The vast majority of a plant's water transport from roots to leaves occurs via the xylem.

Q3: Are xylem and phloem present in all plants?

A: Xylem and phloem, which are true vascular tissues, are the defining characteristic of vascular plants (tracheophytes). This group includes ferns, conifers, and flowering plants. Simpler, non-vascular plants like mosses, liverworts, and hornworts lack a true xylem and phloem system. This is why they are typically very small and must live in moist environments, as they rely on simple diffusion to move water and nutrients short distances.

Q4: Why are the rings of a tree made of xylem?

A: Tree rings are a direct result of the seasonal activity of the vascular cambium, a layer of cells that produces new xylem and phloem. In temperate climates, the cambium produces large, thin-walled xylem cells in the spring (early wood) when water is plentiful, which appear lighter. In the summer, it produces smaller, thicker-walled cells (late wood), which are darker and denser. One light band plus one dark band constitutes one year's growth, forming an annual ring composed entirely of xylem. The phloem is located just inside the bark and is not part of the woody rings.

Conclusion

The functions of xylem and phloem are the cornerstones of plant life, forming a sophisticated and elegant transport system that is both powerful and efficient. The xylem acts as the plant's plumbing and skeleton, passively pulling water and minerals upward from the soil while providing the rigid structure needed to reach for the sky. In contrast, the phloem serves as a dynamic and living distribution network, actively moving energy-rich sugars and vital communication signals from sources to sinks in whichever direction they are needed.

Together, these two vascular tissues are inextricably linked, forming a partnership that enables plants to grow to immense sizes, adapt to changing conditions, and sustain not only themselves but entire ecosystems. From the passive pull of water against gravity to the active, pressure-driven flow of sugary sap, the coordinated work of xylem and phloem is a testament to the remarkable ingenuity of the natural world. Understanding their roles gives us a deeper appreciation for the silent, tireless processes that occur within every leaf, stem, and root around us.

—

Summary of the Article

This article provides a comprehensive explanation of the functions of xylem and phloem, the two key components of a plant's vascular system. It details how the xylem, composed of dead cells, is responsible for the unidirectional (upward) transport of water and minerals through a passive process called transpiration pull, while also providing structural support. In contrast, the phloem, made of living cells, handles the bidirectional transport of sugars and signaling molecules from "sources" to "sinks" through an active mechanism known as the pressure-flow hypothesis. The article highlights the critical differences, the codependent relationship between the two tissues, and their importance in overall plant health and agriculture. A comparative table and a FAQ section are included to further clarify these complex biological functions.