Explaining the Different Types of Plant Root Systems

Of course. As an SEO expert, I will create a comprehensive, engaging, and SEO-optimized article on the different types of plant root systems. The article will be structured according to best practices, ensuring it is valuable for readers and ranks well on search engines.

Here is the article:

—

Beneath the surface of the soil lies a hidden, bustling world that is the very foundation of plant life. This intricate network, the root system, is far more than just a passive anchor; it is a dynamic and vital organ system responsible for nourishment, stability, storage, and communication. For gardeners, farmers, botanists, and anyone curious about the natural world, understanding this subterranean architecture is key to appreciating the resilience and ingenuity of plants. This comprehensive guide is designed to be a definitive resource, where the types of plant root systems explained in clear, accessible detail, revealing the secrets of what happens below ground.

The Fundamental Roles of a Plant's Root System

Before diving into the specific types, it's crucial to understand the universal functions that all root systems perform. These roles are essential for a plant's survival, growth, and reproduction. While we often focus on the visible parts of a plant—the leaves, flowers, and stems—the roots are the unsung heroes working tirelessly underground. Their functions can be broadly categorized into four critical areas: anchorage, absorption, storage, and synthesis.

The most obvious function is anchorage and support. Roots branch out and permeate the soil, creating a strong foundation that holds the plant firmly in place. This is vital to resist the forces of wind, rain, and gravity. A deep and extensive root system acts like the foundation of a building, providing the stability necessary for the plant to grow tall and expose its leaves to sunlight for photosynthesis. Without this firm grip, plants would be easily uprooted and washed away, unable to complete their life cycle.

Equally important is absorption of water and nutrients. The primary purpose of the vast, branching network of roots is to increase the surface area available for absorbing essential resources from the soil. Tiny, single-celled extensions called root hairs dramatically multiply this surface area, acting like microscopic sponges. Through a process called osmosis, water moves from the soil into the roots, carrying dissolved minerals like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. These nutrients are then transported up through the stem to the rest of the plant, fueling its metabolic processes.

Finally, roots serve as critical organs for storage and synthesis. Many plants use their roots as a pantry, storing energy in the form of carbohydrates (like starch and sugar) produced during photosynthesis. This stored energy is crucial for survival during dormant periods (like winter) or to fuel new growth in the spring. Plants like carrots, beets, and radishes are prime examples of this storage function. Furthermore, roots can synthesize important plant hormones, such as cytokinins and gibberellins, which regulate plant growth and development.

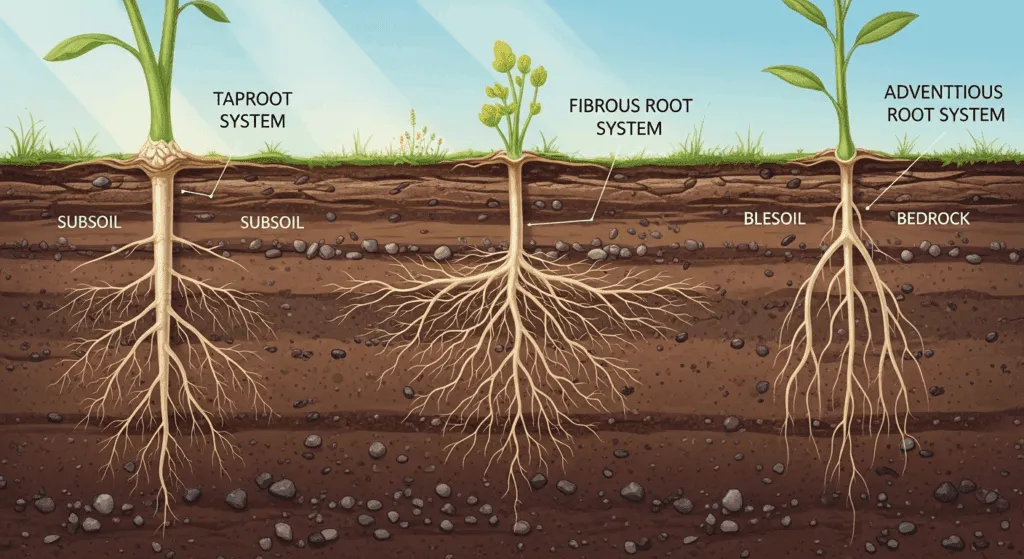

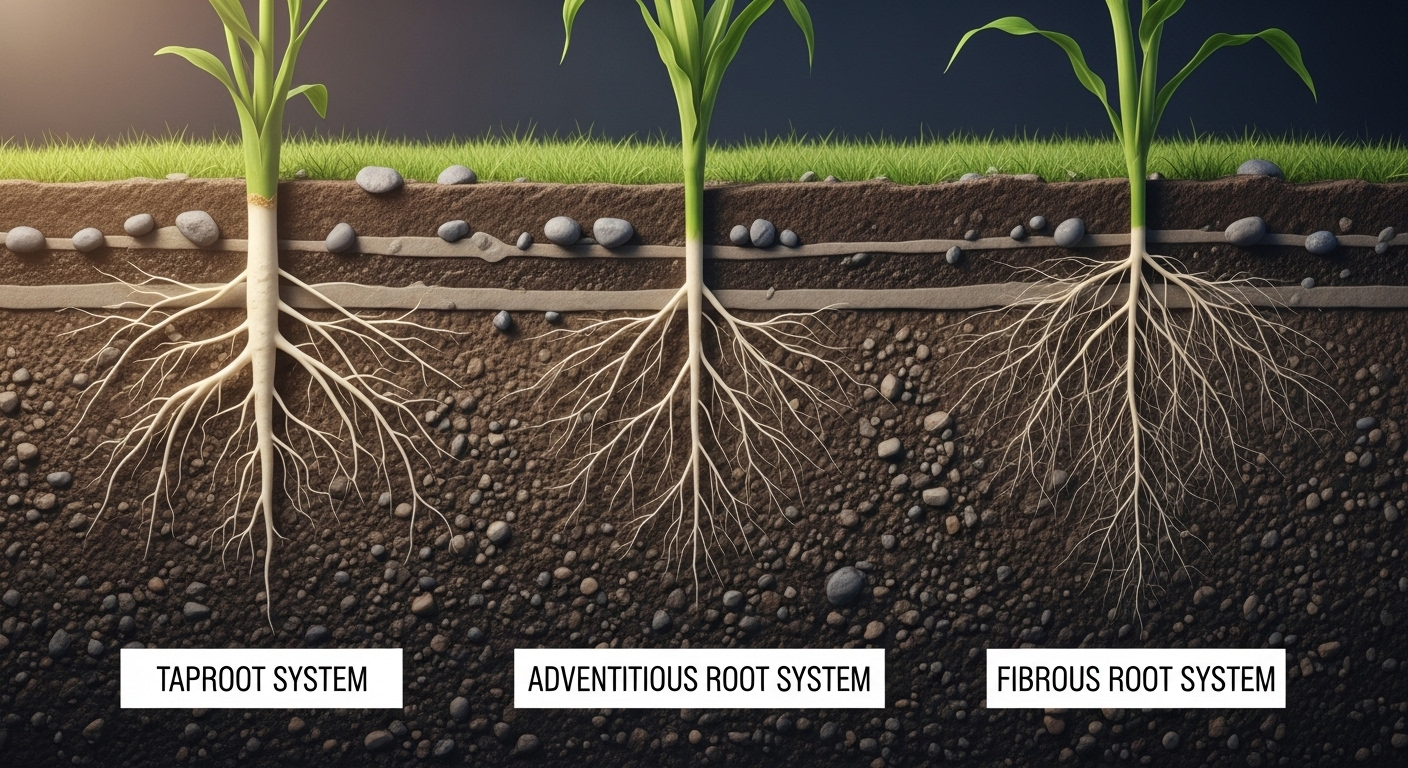

The Two Primary Root Systems: Taproot vs. Fibrous

In the vast kingdom of vascular plants, root systems are first and foremost classified into two primary structures: the taproot system and the fibrous root system. This fundamental division is based on the morphology and development of the roots, originating from the embryonic root, known as the radicle, that emerges from the seed upon germination. Understanding this distinction is the first step in identifying and appreciating the diversity of plant life.

The development path of the radicle determines whether a plant will have a taproot or a fibrous system. In a taproot system, the radicle grows directly downward and enlarges to become the dominant, central root. In a fibrous root system, the primary radicle is short-lived and is soon replaced by a dense cluster of roots that emerge from the base of the stem. This key difference influences everything from how a plant finds water to how it should be cared for in a garden.

This classification is not just a botanical curiosity; it has a strong correlation with the broader classification of flowering plants into dicots and monocots. As a general rule, most dicotyledonous plants (dicots) exhibit a taproot system, while most monocotyledonous plants (monocots) feature a fibrous root system. This connection provides a useful rule of thumb for gardeners and naturalists trying to identify a plant and understand its needs without having to dig it up.

The Taproot System: A Deep Dive

The taproot system is characterized by one main, thick, central root that grows straight down into the soil. This primary root is visibly larger and more dominant than the secondary, lateral roots that branch off from it. The taproot itself can penetrate deep into the soil profile, sometimes for several meters, in search of water tables and nutrients that are unavailable near the surface. This structure is a significant advantage in environments with infrequent rainfall, as it allows the plant to access deeper, more reliable water sources.

Classic examples of plants with taproot systems include dandelions, carrots, parsnips, radishes, and many species of trees like oaks and pines. In the case of carrots and radishes, the taproot is also a modified storage organ, swollen with starches and sugars. For a plant like the dandelion, its notoriously long taproot is what makes it so difficult to eradicate from a lawn; if even a small piece of the taproot is left behind, it has the ability to regenerate the entire plant. This deep anchoring also makes plants with taproots exceptionally sturdy and resistant to being uprooted.

The Fibrous Root System: A Widespread Network

In stark contrast, the fibrous root system is a dense, web-like mass of thin, moderately branching roots that all grow from the base of the stem. There is no single, dominant primary root. Instead, a large number of roots of similar size and length form a mat just below the soil surface. This structure is incredibly efficient at holding soil particles together, which is why grasses are so effective at preventing soil erosion on hillsides and riverbanks.

Plants with fibrous root systems are excellent at capturing surface water from rainfall before it can percolate deeper into the soil. This makes them highly competitive in environments where moisture is primarily available in the topsoil. Common examples include all grasses (like lawn grass, wheat, and corn), rice, onions, and lilies. Because the entire root system can be contained within a relatively shallow area, transplanting plants with fibrous roots can be challenging, as it's difficult to extract the entire root mass without significant damage.

Exploring Modified and Specialized Root Systems

While taproot and fibrous systems form the primary framework, the ingenuity of nature has led to a fascinating array of modifications. These specialized roots are evolutionary adaptations that allow plants to thrive in challenging and unique environments, such as waterlogged swamps, arid deserts, or even without any soil at all. These modifications are not entirely new systems but are often adaptations of the primary taproot or fibrous structures to perform specialized functions beyond the basics of anchorage and absorption.

These adaptations showcase the incredible plasticity of plant anatomy. Roots can be modified for extraordinary storage capacity, for breathing air in oxygen-poor environments, for providing additional structural support, or for climbing and attaching to other surfaces. Studying these modified roots gives us a deeper appreciation for how plants have conquered nearly every habitat on Earth by re-engineering their fundamental organs to meet specific environmental pressures.

Storage Roots: The Plant's Pantry

Many plants have evolved roots specifically modified for the storage of food (usually starch) or water. These storage roots become thick, fleshy, and swollen with reserves to help the plant survive dormant periods or droughts. This modification can occur in both taproot and fibrous root systems.

<strong>Taproot Storage:</strong> The most familiar examples are "root vegetables" like carrots (Daucus carota), beets (Beta vulgaris), and turnips (Brassica rapa*). In these plants, the primary taproot is the main site of carbohydrate storage.

<strong>Fibrous Storage:</strong> In other plants, it is the fibrous roots that become swollen with nutrients. These are often calledtuberous roots. The sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas*) is a perfect example. Unlike a regular potato, which is a modified stem (a tuber), the sweet potato is a true root. Dahlias and cassavas also produce tuberous roots.

Adventitious and Prop Roots: Above-Ground Support

Adventitious roots are roots that arise from any part of the plant other than the primary root or its branches, such as from a stem or a leaf. This category includes several important modifications, one of the most striking being prop roots.

Prop roots grow down from the lower part of the stem and "prop" the plant up, providing extra stability. They are common in plants that are tall and slender or that grow in unstable, loose soil. Corn plants (Zea mays) develop prop roots from their lower nodes to help support their tall stalks. A more dramatic example is the Red Mangrove (Rhizophora mangle), which lives in tidal mudflats. Its extensive network of arching prop roots not only anchors the tree in the soft mud but also helps to aerate the root system.

Aerial and Epiphytic Roots: Life in the Air

As the name suggests, aerial roots are roots that grow entirely or partially above the ground. They are a common feature of epiphytic plants—plants that grow on other plants (like trees) for physical support without being parasitic.

The most well-known examples are the roots of many orchids. These thick, spongy aerial roots are covered by a layer of dead cells called the velamen, which can rapidly absorb moisture and nutrients from the humid air and rainfall. Other plants, like English ivy (Hedera helix), develop aerial roots that act as holdfasts, cementing the climbing stem to walls, rocks, or tree bark. The Banyan tree (Ficus benghalensis) produces massive aerial roots that grow down from the branches, eventually reaching the ground and thickening to become pillar-like trunks, supporting the tree's enormous canopy.

Pneumatophores: Roots That Breathe

In habitats like swamps, marshes, and coastal wetlands, the soil is often waterlogged and anaerobic (lacking oxygen). Plants living in these conditions face the challenge of root suffocation. To overcome this, some species have evolved pneumatophores, also known as "air roots" or "breathing roots."

These are specialized root branches that grow vertically upwards, breaking the surface of the water or mud. They are equipped with numerous pores (lenticels) that allow for the exchange of gases, enabling the submerged parts of the root system to obtain the oxygen necessary for respiration. The Bald Cypress (Taxodium distichum), famous for its "knees" that protrude from the swamp water, and various mangrove species are classic examples of plants that utilize pneumatophores to survive in their challenging, oxygen-deprived environments.

The Connection Between Root Systems and Plant Classification

The distinction between taproot and fibrous root systems is one of the most reliable and observable characteristics used to differentiate between the two major classes of flowering plants: Dicotyledons (Dicots) and Monocotyledons (Monocots). While there are always exceptions in biology, this correlation provides a powerful diagnostic tool for identifying a plant and predicting its other characteristics.

Dicots, which start life with two embryonic leaves (cotyledons) in their seed, almost always exhibit a taproot system. Other common traits of dicots include leaves with netted or branched vein patterns and flower parts that occur in multiples of four or five. Examples of dicots are abundant and include beans, roses, tomatoes, oak trees, and sunflowers. If you see a plant with branching veins on its leaves, you can be fairly certain it has a taproot system beneath the soil.

Conversely, Monocots begin with a single embryonic leaf (cotyledon) and are characterized by a fibrous root system. Their other features typically include long, slender leaves with parallel veins and flower parts arranged in multiples of three. The monocot group includes all grasses, corn, wheat, rice, lilies, orchids, and onions. If you examine a blade of grass or a corn leaf, you will see the veins run parallel to each other, a tell-tale sign of a fibrous root system below.

Table: Taproot vs. Fibrous Root System at a Glance

| Feature | Taproot System | Fibrous Root System |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Root | A single, dominant primary root (the taproot) persists and grows deeply. | The primary root is short-lived and replaced by many smaller roots. |

| Origin | The primary root develops directly from the embryonic radicle. | Roots arise from the base of the stem (adventitious origin). |

| Depth | Grows deep into the soil. | Typically shallow, forming a mat near the surface. |

| Main Function | Deep water access and strong anchorage. | Surface water absorption and soil erosion control. |

| Typical Plant Group | Dicotyledons (Dicots) | Monocotyledons (Monocots) |

| Examples | Carrot, Dandelion, Oak Tree, Rose, Radish | Grass, Corn, Wheat, Onion, Lily |

Practical Applications: Why Understanding Root Systems Matters

This botanical knowledge is not just for academic purposes; it has significant practical implications for gardening, agriculture, and environmental management. Understanding a plant's root system can mean the difference between success and failure in cultivation and conservation efforts.

For the home gardener, knowing the root type influences many decisions. Plants with deep taproots, like carrots, require deep, loose, well-tilled soil to develop properly. They are also more drought-tolerant once established but can be difficult to transplant without damaging the crucial primary root. Conversely, plants with shallow fibrous roots, like lettuce or onions, require more frequent, shallow watering and are better suited for wider, shallower containers. Their dense root mass also makes them more challenging to weed around without disturbing the plant.

In agriculture, root systems are central to crop selection and soil management. Farmers may plant crops with fibrous roots, like rye or clover, as cover crops to prevent soil erosion and improve soil structure during the off-season. Tillage practices are also affected; no-till farming, for example, helps preserve the complex soil ecosystem and the root channels created by previous crops, improving water infiltration and soil health for future plantings with both taproots and fibrous roots.

In environmental science, this knowledge is applied in ecosystem restoration and phytoremediation. To stabilize a degraded hillside, ecologists will choose plants with dense, soil-binding fibrous root systems. For cleaning contaminated soil (phytoremediation), scientists may select plants with deep taproots that can reach and absorb pollutants from lower soil layers. The successful restoration of wetlands relies on planting species like mangroves and cypress, whose specialized prop roots and pneumatophores are perfectly adapted to that unique environment.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Can a plant have both a taproot and fibrous roots?

A: In a sense, yes. A taproot system consists of a large, primary taproot, but it also has many smaller, branching lateral roots that grow out from it. These lateral roots function similarly to a fibrous system, helping to absorb water and nutrients in the surrounding soil. So, a taproot system is best described as a dominant taproot with fibrous lateral roots.

Q: What is the difference between a root and a tuber, like a potato?

A: This is a common point of confusion. A storage root (like a sweet potato or carrot) is a true root that has been modified to store food. A tuber (like a regular potato) is a modified, swollen underground stem. You can tell the difference because a potato has "eyes," which are actually nodes with buds from which new stems and leaves can grow. True roots do not have nodes or buds.

Q: How deep can plant roots grow?

A: It varies tremendously depending on the plant species and soil conditions. Annual garden plants may have roots that go down a foot or two. A large oak tree can have roots extending dozens of feet deep and even wider. The record-holder is the Shepherd's Tree in the Kalahari Desert, whose roots have been found to reach depths of over 220 feet (about 68 meters) to find water.

Q: Do all plants have roots?

A: No, not all plants have true roots. Non-vascular plants, such as mosses and liverworts, lack true roots, stems, and leaves. Instead, they have simple, threadlike structures called rhizoids that primarily serve to anchor them to a surface but are not efficient at water absorption. Some free-floating aquatic plants, like the Bladderwort, also lack roots.

Q: How can I tell what root system my plant has without digging it up?

A: The easiest way is to look at its leaves. If the plant has leaves with veins that form a branched, net-like pattern, it is most likely a dicot and has a taproot system. If the leaves have veins that run in straight, parallel lines (like a blade of grass), it is most likely a monocot and has a fibrous root system.

Conclusion

The world of plant roots is a testament to the power of evolution and adaptation. From the single, determined plunge of a taproot to the intricate, soil-gripping web of a fibrous system, roots are the essential, life-sustaining foundation of the plant kingdom. The specialized modifications—from aerial roots that drink from the air to pneumatophores that breathe for the plant—demonstrate an incredible ability to solve environmental challenges. By understanding these hidden structures, we gain more than just botanical knowledge; we gain a practical guide for better gardening, more sustainable agriculture, and a deeper appreciation for the complex, interconnected web of life that thrives, often unseen, right beneath our feet.

—

Article Summary

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the different types of plant root systems. It begins by outlining the four fundamental roles of any root system: anchorage, absorption, storage, and synthesis. The guide then details the two primary classifications: the taproot system, characterized by a single, deep primary root typical of dicots like carrots and oaks, and the fibrous root system, a dense, shallow network of roots common in monocots like grasses and corn. The article further explores a variety of fascinating specialized and modified roots, including storage roots (sweet potatoes), adventitious prop roots (corn, mangroves), aerial roots (orchids), and breathing pneumatophores (cypress). A comparative table, practical applications for gardening and agriculture, and a detailed FAQ section are included to provide a holistic and practical understanding of these vital subterranean structures.