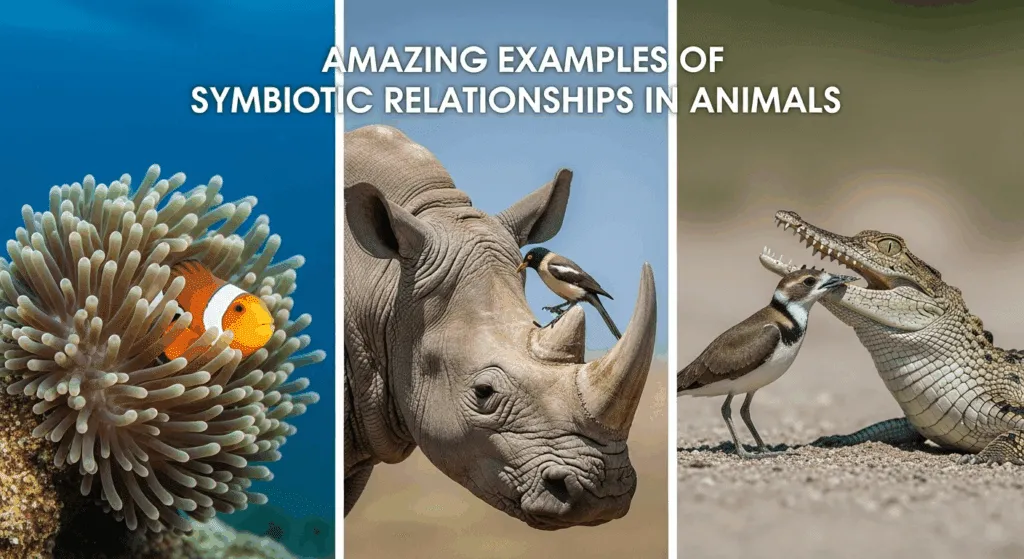

Amazing Examples of Symbiotic Relationships in Animals

In nature, the idea of the "lone wolf" is often more myth than reality. The vast, intricate web of life is woven not just from competition, but from cooperation, dependence, and complex interactions between different species. Survival is a team sport, and many animals have evolved to form extraordinary partnerships that help them find food, defend against predators, or simply have a place to live. These fascinating examples of symbiotic relationships in animals are not rare exceptions; they are fundamental to the health and balance of ecosystems all over the world, from the deepest oceans to the highest mountains. Understanding these relationships reveals a world far more interconnected and collaborative than we might imagine.

What is Symbiosis? The Three Main Types

The term symbiosis, derived from Greek words meaning "living together," describes any long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms. This broad definition covers a wide spectrum of relationships, from mutually beneficial partnerships to one-sided, harmful ones. Ecologists and biologists typically classify these interactions into three main categories based on the outcome for each participant: mutualism, commensalism, and parasitism. This framework helps us understand the costs and benefits that drive these incredible animal pairings.

It's crucial to recognize that these relationships are not static. They are the product of millions of years of co-evolution, where two or more species reciprocally affect each other's evolutionary path. For instance, as a flower evolves a deeper shape, its pollinator might evolve a longer beak or tongue to reach the nectar. This dynamic interplay is what makes the study of symbiosis so compelling. It's a living, breathing testament to nature's ability to innovate and adapt, creating stability and resilience within complex food webs.

While we often think of animals when we hear about symbiosis, these relationships exist across all kingdoms of life, involving plants, fungi, bacteria, and other microorganisms. However, the interactions in the animal kingdom are often the most dramatic and visually striking. By examining the three primary types, we can build a strong foundation for appreciating the specific, amazing examples that nature has to offer, each telling a unique story of survival and interdependence.

Mutualism: A Win-Win Partnership

Mutualism is the classic "you scratch my back, I'll scratch yours" scenario. In a mutualistic relationship, both species involved derive a significant benefit from the interaction. This benefit often leads to an increased chance of survival and reproduction for both parties. These partnerships can be so tightly integrated that one species cannot survive without the other, a condition known as obligate mutualism. This is the most celebrated type of symbiosis because it highlights cooperation as a powerful evolutionary force.

The benefits exchanged in mutualistic relationships are diverse. They can involve:

<strong>Trophic mutualism:</strong> Where partners specialize in complementary ways to obtain energy and nutrients. A classic example is the relationship between coral polyps and thezooxanthellae* algae living within them. The algae photosynthesize, providing food for the coral, while the coral provides a protected environment and compounds needed for photosynthesis.

- Defensive mutualism: Where one partner receives food or shelter in return for defending its partner against predators or parasites.

- Dispersive mutualism: Where one species receives food in return for transporting the pollen or seeds of its partner, as seen with bees and flowers.

Commensalism: One Benefits, the Other is Unaffected

Commensalism describes a relationship where one organism benefits, and the other is neither helped nor harmed—it's essentially neutral. The term comes from the Latin commensalis, meaning "sharing a table." This is a more subtle form of symbiosis, as the host organism might not even be aware of its guest's presence. The benefiting organism, known as the commensal, often uses the host for transportation, housing, or to acquire food that the host has left behind.

Because the host is unharmed, there is often no evolutionary pressure for it to develop defenses to prevent the relationship. For the commensal, this is a highly effective, low-energy strategy for survival. For example, a bird building a nest in a tree benefits from the shelter and support provided by the tree, but the tree is generally unaffected by the nest. This type of interaction is extremely common in nature, though it can sometimes be difficult to distinguish from a very mild form of mutualism or parasitism, as even a seemingly neutral interaction might have tiny, difficult-to-measure effects.

Parasitism: A One-Sided, Harmful Relationship

Parasitism is the "dark side" of symbiosis. In this type of relationship, one organism, the parasite, benefits at the expense of the other, the host. The parasite lives on or inside the host's body, deriving nutrients and shelter from it. Unlike a predator, a parasite typically does not kill its host, at least not immediately. A successful parasite is one that can exploit its host for as long as possible without triggering a fatal immune response or causing its host to die too quickly, as the host's death would mean the end of the parasite's food supply.

Parasites have developed an incredible array of adaptations to find hosts, attach to them, and evade their immune systems. This relationship exerts strong evolutionary pressure on the host to develop defenses, leading to a continuous "evolutionary arms race" between the two species. While we often have a negative view of parasites, they play a critical role in ecosystems by regulating host populations and promoting biodiversity. This relationship is incredibly common; in fact, it's estimated that a large percentage of all species on Earth are parasitic in some way.

Classic Examples of Mutualism in Action

Mutualistic relationships are some of the most inspiring stories of cooperation in the animal kingdom. They demonstrate how different species can evolve together to overcome challenges, creating partnerships that are greater than the sum of their parts. These interactions are often highly specialized and have been refined over countless generations into a near-perfect system of exchange.

From the vibrant coral reefs to the vast African savanna, mutualism is a key driver of ecological function. These partnerships can be a source of food, protection, or even hygiene, allowing the participants to thrive in ways they couldn't on their own. The following examples showcase the sheer ingenuity of nature and the powerful benefits of working together.

Observing these relationships gives us a window into the complex negotiations of nature. What does each partner gain? What do they give up? How did this intricate dance evolve? Each example is a case study in co-evolution, highlighting the delicate balance required to maintain a successful and lasting partnership in the wild.

The Clownfish and the Sea Anemone: An Iconic Duo

Perhaps one of the most famous examples of symbiotic relationships in animals, popularized by the movie Finding Nemo, is the partnership between the clownfish and the sea anemone. Sea anemones possess venomous tentacles armed with stinging cells called nematocysts, which they use to capture prey and deter predators. Most fish that blunder into an anemone are quickly paralyzed and consumed. The clownfish, however, is immune.

The clownfish protects itself by developing a thick layer of mucus on its skin. Scientists believe this mucus is either based on sugar rather than protein, so the anemone doesn't recognize it as food, or that the fish slowly and carefully acclimates to a specific anemone, incorporating its chemicals into its own slime coat to trick the anemone into thinking the fish is a part of itself. In return for this safe, protected home, the clownfish provides several services. It aggressively defends the anemone from butterflyfish and other predators that might try to eat its tentacles. The clownfish also helps keep the anemone clean from parasites and may even lure smaller fish into the anemone's stinging embrace, providing it with a meal.

The Oxpecker and Large Mammals: A Flying Alarm System

On the savannas of Africa, it’s common to see small birds, known as oxpeckers, riding on the backs of large mammals like rhinos, zebras, giraffes, and buffalo. This is a classic example of mutualism. The oxpecker gets an easy meal by feeding on ticks, flies, and other parasites that live on the mammal's skin. This provides a clear benefit to the host animal, as it gets rid of irritating and potentially disease-carrying pests. This is a mobile cleaning service.

But the benefits don't stop at pest control. The oxpecker also acts as a vigilant security guard. With its keen eyesight, it can spot predators from a distance. When it senses danger, it lets out a loud, hissing cry, alerting its much larger and less observant host to the threat. This early warning system gives the mammal precious extra seconds to prepare for a defense or to flee. Recent studies have shown that rhinos carrying oxpeckers are significantly better at detecting and avoiding human poachers, making this relationship a crucial factor in their survival.

The Honeyguide and the Honey Badger (or Humans): A Sweet Collaboration

The relationship between the Greater Honeyguide bird and the honey badger is a remarkable example of interspecies communication and cooperation. The honeyguide loves to eat beeswax and bee larvae, but it's too small to break into the heavily defended beehives on its own. The honey badger, on the other hand, is a powerful and fearless predator with thick skin that can withstand bee stings, but it has trouble finding the hives. This is where the partnership begins.

The honeyguide finds a beehive and then seeks out a nearby honey badger. It gets the badger's attention with a specific chattering call and then performs a series of short flights, leading the mammal directly to the nest. Once they arrive, the honey badger uses its powerful claws to tear the hive apart, feasting on the honey. After the badger has had its fill, the honeyguide moves in to eat the leftover wax and grubs. Incredibly, this relationship isn't exclusive to honey badgers; honeyguides have been known to form the same partnership with humans in some parts of Africa, guiding local honey-hunters to hives in exchange for a share of the spoils.

Exploring Commensalism: The Art of Hitchhiking and Housing

Commensal relationships are often less dramatic than mutualism or parasitism, but they are just as widespread and fascinating. They showcase an organism's ability to capitalize on an opportunity without causing any disturbance. This "free ride" strategy is all about energy conservation and clever positioning. The commensal species finds a way to use the host for transport, shelter, or simply as a mobile platform from which to gather food.

These relationships highlight the diverse ways animals have adapted to their environments. Instead of competing for resources, these species have found a way to coexist peacefully, with one party gaining a subtle advantage. From the open ocean to dense forests, examples of commensalism are everywhere, demonstrating that sometimes, the best strategy is simply to go along for the ride.

Remora Fish and Sharks: The Ultimate Hitchhikers

The remora is a fish with a remarkable adaptation: a modified dorsal fin that has evolved into a powerful suction cup on the top of its head. This allows it to attach itself firmly to larger marine animals, most commonly sharks, but also manta rays, whales, and sea turtles. This is a classic example of commensalism. The remora gains a significant benefit: free transportation through the ocean. This saves the remora an enormous amount of energy.

In addition to transport, the remora benefits by feeding on scraps of food left behind when its host makes a kill. It also gains protection from predators, as few would dare to attack a fish attached to a large shark. For its part, the shark is almost entirely unaffected. The remora is small and streamlined, creating negligible drag, and it does not harm the shark's skin or steal its food directly. The shark simply serves as a mobile home and dining vehicle for its smaller, opportunistic companion.

Barnacles on Whales: A Mobile Home with a View

Barnacles are crustaceans that, in their adult stage, are sessile, meaning they permanently attach themselves to a hard surface. While many attach to rocks or ship hulls, some species have specialized in attaching to the skin of living animals, particularly large, slow-moving whales like humpbacks and gray whales. This is a commensal relationship where the barnacle is the clear beneficiary.

By attaching to a whale, the barnacle gets a free ride through nutrient-rich waters. As filter feeders, this constant movement brings a steady supply of plankton directly to them, a much more efficient feeding strategy than waiting for currents to bring food to a static rock. The whale, on the other hand, appears to be unharmed. While a heavy load of barnacles might create a tiny amount of extra drag in the water, it is not considered significant enough to negatively impact the massive whale's health or survival. The barnacles essentially get a mobile home with a panoramic ocean view and a constant food delivery service, all at no cost to their host.

The Dark Side of Symbiosis: Examples of Parasitism

While cooperation is common in nature, so is exploitation. Parasitism is a stark reminder that survival is often a ruthless game. In these relationships, the parasite thrives by draining resources from its host, often causing chronic illness, weakness, and, in some cases, bizarre behavioral changes. These relationships are defined by a clear winner and a clear loser.

The world of parasites is vast and incredibly diverse, ranging from external blood-suckers to internal worms and even creatures that replace entire organs. Their life cycles are often complex, sometimes involving multiple hosts to complete their development. The following examples offer a glimpse into the strange and sometimes horrifying world of parasitism.

The Tick and its Host: A Blood-Sucking Problem

Ticks are one of the most well-known ectoparasites (parasites that live on the outside of their host). These small arachnids feed on the blood of mammals, birds, and reptiles. A tick's survival depends entirely on its ability to find a host, latch on, and feed undetected for several days. They use specialized mouthparts to pierce the host's skin and secrete saliva that contains both an anticoagulant to keep blood flowing and an anesthetic to prevent the host from feeling the bite.

While the tick gets a vital blood meal, the host suffers. The immediate harm is the loss of blood and potential skin irritation. However, the greater danger lies in the diseases ticks can transmit. Ticks are vectors for a variety of serious illnesses, including Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and anaplasmosis. In this relationship, the tick benefits enormously while the host is harmed and put at risk of disease, making it a clear and dangerous example of parasitism.

The Cymothoa exigua (Tongue-Eating Louse): A True Body Snatcher

For a truly bizarre and gruesome example of parasitism, look no further than the Cymothoa exigua, an isopod crustacean often called the "tongue-eating louse." This parasite's life cycle is the stuff of nightmares. It enters a fish, typically a rose snapper, through its gills and attaches itself to the base of the fish's tongue. It then uses its claws to sever the blood vessels in the tongue, causing the organ to atrophy and fall off due to lack of blood.

But the horror doesn't end there. The parasite then firmly attaches itself to the stub of the tongue and effectively becomes the fish's new, functional tongue. The fish can manipulate the parasite just like it would its original tongue, using it to help swallow food. The parasite survives by feeding on the fish's blood or on the mucus in its mouth. This is the only known case of a parasite functionally replacing a host's organ. The fish is kept alive, albeit with a monstrous new appendage in its mouth, allowing the parasite to thrive.

The Nuances and Complexities of Symbiosis

While the three categories of mutualism, commensalism, and parasitism provide a useful framework, nature is rarely so black and white. Many symbiotic relationships exist on a spectrum, and their classification can change depending on the context, the environment, or even the age of the organisms involved. What was once thought to be a clear-cut case of commensalism might, upon closer inspection, reveal subtle mutualistic benefits or minor parasitic costs.

For example, the relationship between the oxpecker and large mammals was long held as a perfect example of mutualism. However, more recent observations have complicated this picture. Scientists have found that oxpeckers don't just eat parasites; they also peck at wounds and drink the blood of their hosts, a behavior that can slow down healing and increase the risk of infection. So, is the oxpecker a helpful cleaner, a "flying vampire," or both? The answer is likely somewhere in the middle. The relationship may be mutualistic when the parasite load is high and parasitic when it is low.

This "symbiotic continuum" highlights the dynamic and ever-evolving nature of these interactions. A relationship can shift from one category to another based on resource availability or environmental stress. This complexity is what makes an ecosystem resilient. The table below provides a simplified comparison, but it's important to remember the gray areas that exist in the real world.

| Relationship Type | Organism A (Beneficiary/Parasite) | Organism B (Partner/Host) | Summary of Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | Receives Benefit (+) | Receives Benefit (+) | Both species gain a clear advantage (e.g., food, defense). |

| Commensalism | Receives Benefit (+) | Unaffected (0) | One species benefits without affecting the other. |

| Parasitism | Receives Benefit (+) | Is Harmed (-) | One species benefits by exploiting and harming the other. |

Ultimately, these classifications are human-made labels we apply to a deeply complex and fluid natural world. Studying these nuances helps us appreciate that every interaction, no matter how small, contributes to the overall structure and function of an ecosystem.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Is symbiosis always between two different animal species?

A: Not at all. Symbiosis is a broad term for any long-term interaction between different biological species. This frequently involves an animal and a non-animal. For example, the mutualism between corals (animals) and zooxanthellae (algae) is fundamental to reef ecosystems. Similarly, the bacteria in the gut of a cow (animal) that help it digest cellulose are in a symbiotic relationship. These interactions across different kingdoms of life are just as common and important as animal-animal partnerships.

Q2: Can a symbiotic relationship change over time from one type to another?

A: Yes, this is a key concept in ecology. An interaction that is mutualistic in one environment might become commensal or even parasitic in another. For example, the oxpecker relationship can be mutualistic when there are many ticks on a rhino, but parasitic when the oxpeckers start feeding on the rhino's blood because ticks are scarce. These shifts are driven by the changing costs and benefits for each partner, influenced by factors like resource availability, predator presence, and overall ecosystem health.

Q3: What is the most common type of symbiosis?

A: While mutualism gets a lot of attention for its feel-good stories of cooperation, parasitism is widely believed to be the most common lifestyle on Earth. Scientists estimate that a huge percentage of all species, perhaps more than half, are parasitic at some stage of their life. This is because every free-living organism represents a potential habitat and food source for a parasite. The incredible diversity of parasites, from viruses and bacteria to worms and insects, makes this a staggeringly successful evolutionary strategy.

Conclusion

The natural world is a testament to the power of connection. From the life-saving alarm call of an oxpecker to the sinister replacement a fish's tongue by a louse, examples of symbiotic relationships in animals paint a vivid picture of interdependence. These partnerships, whether they are win-win, win-neutral, or win-lose, are not mere curiosities; they are the essential threads that hold ecosystems together. They drive evolution, regulate populations, and create a level of complexity and resilience that is both awe-inspiring and vital for the planet's health.

By moving beyond a simple view of nature as a realm of "survival of the fittest" defined only by competition, we begin to see a more nuanced and accurate reality. It is a world where cooperation can be as powerful a force as conflict, where an organism's greatest ally might be a member of a completely different species. These intricate dances of survival remind us that no creature is an island and that the web of life is bound together in ways both strange and spectacular.

***

Summary

This article, "Amazing Examples of Symbiotic Relationships in Animals," provides an in-depth exploration of symbiosis, the long-term interaction between different species. It begins by defining the three main types of symbiotic relationships: mutualism (both benefit), commensalism (one benefits, the other is unaffected), and parasitism (one benefits at the host's expense).

The article then dives into detailed examples for each category. For mutualism, it covers the iconic partnership between the clownfish and sea anemone, the oxpecker bird acting as a cleaner and alarm system for large mammals, and the unique collaboration between the honeyguide bird and honey badgers. For commensalism, it examines the remora fish hitchhiking on sharks and barnacles using whales as mobile homes. For parasitism, it highlights the dangers of ticks and the bizarre case of the Cymothoa exigua, a louse that replaces a fish's tongue.

A dedicated section discusses the nuances of these relationships, explaining that they exist on a continuum and can change based on environmental context. This is supported by a comparative table. The article concludes with an FAQ section to address common questions and a final summary reinforcing that these complex partnerships are fundamental to the structure, function, and resilience of ecosystems worldwide.