How Photosynthesis Works: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

Life on Earth is a vibrant tapestry of interconnected systems, but a single, silent process powers almost all of it: photosynthesis. This remarkable biological alchemy, performed by plants, algae, and some bacteria, converts simple sunlight into the chemical energy that fuels ecosystems, builds biomass, and produces the very air we breathe. It's a process so fundamental that without it, the world as we know it would cease to exist. But how does this solar-powered engine for life actually function? To truly appreciate this marvel, we need to understand how does photosynthesis work step by step, from the first photon of light striking a leaf to the final creation of a sugar molecule.

This article will serve as your comprehensive guide, breaking down this complex process into understandable stages. We will journey inside the microscopic world of the plant cell, explore the two major acts of this biochemical drama, and uncover the critical factors that can influence its efficiency. Prepare to demystify the magic that happens in every green leaf around you.

What is Photosynthesis? The Foundation of Life on Earth

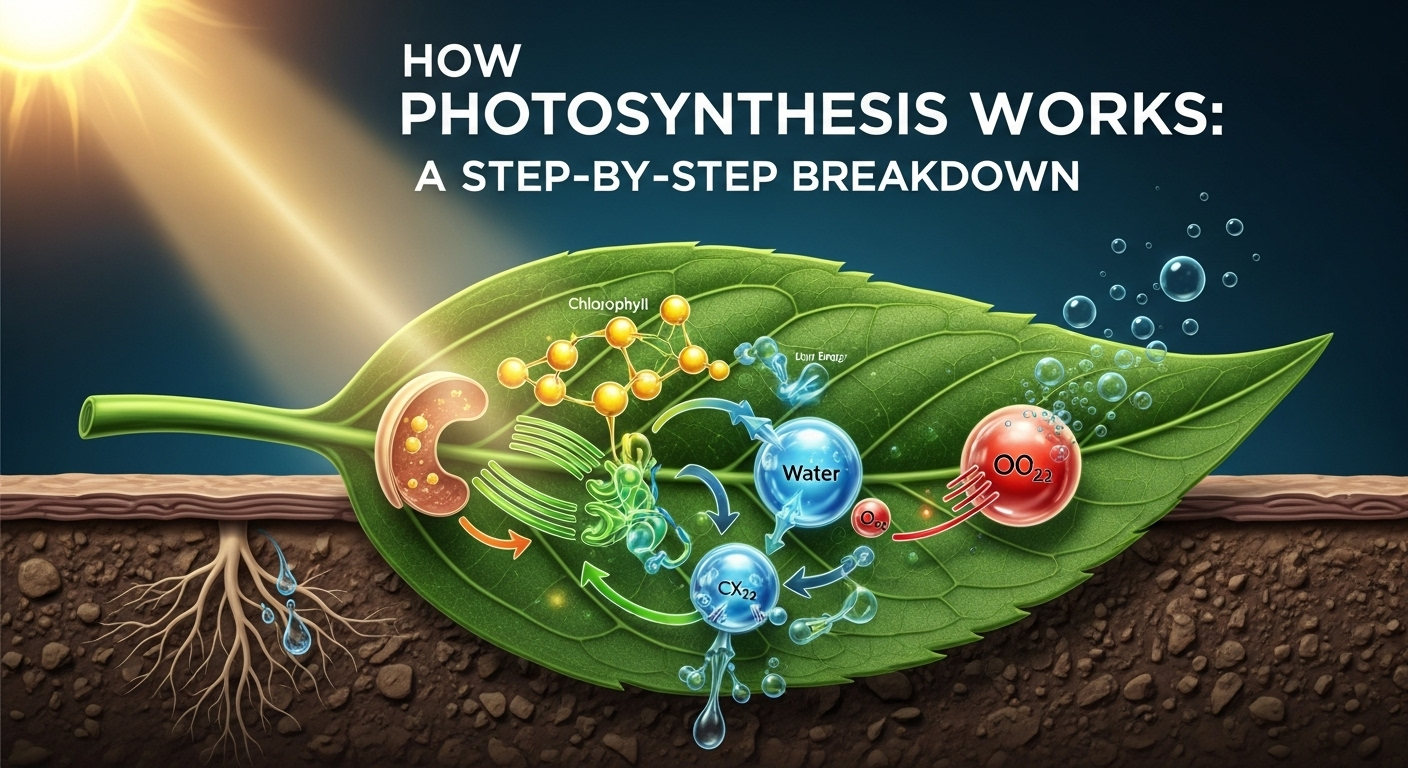

At its core, photosynthesis is the process used by photoautotrophs—organisms that make their own food using light—to convert light energy into chemical energy. This chemical energy is then stored in the bonds of carbohydrate molecules, such as glucose (sugar), which the organism can use for fuel. The overall process can be summarized by a deceptively simple chemical equation: 6CO₂ + 6H₂O + Light Energy → C₆H₁₂O₆ + 6O₂. This tells us that six molecules of carbon dioxide and six molecules of water, in the presence of light, produce one molecule of glucose and six molecules of oxygen.

The importance of this conversion cannot be overstated. The glucose produced is the primary source of energy for the plant itself, fueling its growth, reproduction, and all other metabolic activities. When animals eat plants (or eat animals that have eaten plants), they are essentially transferring this stored solar energy into their own bodies. This makes photosynthesis the ultimate source of energy for nearly every food chain on the planet. Furthermore, the oxygen released as a byproduct is crucial for aerobic respiration, the process most organisms, including humans, use to unlock energy from food.

To pull off this incredible feat, plants require three key ingredients, often called reactants. The first is light energy, typically from the sun, which acts as the catalyst for the entire reaction. The second is carbon dioxide (CO₂) , a gas that plants absorb from the atmosphere through tiny pores on their leaves called stomata. The third ingredient is water (H₂O), which is primarily absorbed from the soil through the plant's roots. From these simple, inorganic inputs, the plant's internal machinery masterfully constructs complex organic molecules, with glucose and oxygen being the life-sustaining outputs, or products.

The Photosynthetic Powerhouse: Inside the Chloroplast

To understand where the magic of photosynthesis happens, we must zoom in from the whole plant to a single leaf, then to a single cell, and finally, to a specialized organelle within that cell: the chloroplast. These tiny, oval-shaped structures are the dedicated factories for photosynthesis in plant and algal cells. A typical plant cell in a leaf can contain dozens or even hundreds of chloroplasts, each working tirelessly to convert sunlight into usable energy. The green color we associate with plants is due to the pigment chlorophyll, which is densely packed within these chloroplasts and is essential for capturing light.

The structure of the chloroplast is perfectly designed for its function, featuring a complex system of internal membranes. It is enclosed by a double membrane—an outer and an inner membrane—that regulates the passage of materials in and out. The fluid-filled space within the inner membrane is called the stroma. It's a dense, enzyme-rich soup where the second major stage of photosynthesis occurs. Suspended within this stroma is a third membrane system, consisting of flattened, sac-like structures called thylakoids. These are the critical sites for the first stage of photosynthesis.

Thylakoids are often arranged in stacks, much like a stack of coins, known as grana (singular: granum). The membrane of each thylakoid contains the chlorophyll molecules and other protein complexes that form the light-capturing machinery. The space inside a thylakoid is called the thylakoid lumen. This intricate arrangement of membranes and compartments—the stroma, the thylakoids, and the lumen—allows the plant to create chemical gradients and segregate the different stages of photosynthesis, maximizing efficiency and control over the entire process.

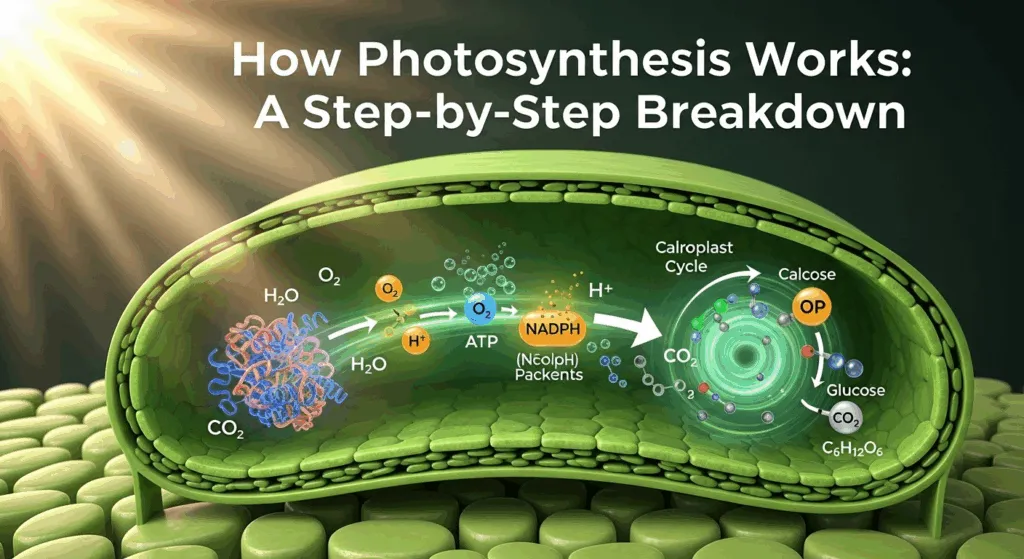

The First Act: The Light-Dependent Reactions

The first major phase of photosynthesis is aptly named the light-dependent reactions because, as the name suggests, it directly requires light to proceed. This stage is all about converting light energy into short-term chemical energy. Think of it as charging a battery. The primary location for this act is within the thylakoid membranes inside the chloroplasts. Here, the energy from photons of light is captured and used to create two vital energy-carrying molecules: ATP (adenosine triphosphate) and NADPH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate). Oxygen is also released as a crucial byproduct during this stage.

These reactions are a rapid and elegant sequence of events involving multiple protein complexes and electron carriers embedded in the thylakoid membrane. The entire process is driven by the energy of sunlight, which excites electrons and initiates a flow of energy through a system known as an electron transport chain. Let's break down this first act into its key scenes.

Light Absorption and Electron Excitation

The process begins when a photon of light strikes a pigment molecule, primarily chlorophyll, located within large protein complexes called photosystems. There are two types of photosystems involved: Photosystem II (PSII) and Photosystem I (PSI), which, despite their names, work in sequence with PSII acting first. When chlorophyll absorbs light energy, it doesn't get hot; instead, the energy is used to boost one of its electrons to a higher, more energetic state. This "excited" electron is now unstable and ready to be passed along to another molecule.

This transfer of energy is incredibly efficient. Within the photosystem, numerous antenna pigment molecules (chlorophylls and carotenoids) capture photons and funnel the energy to a special pair of chlorophyll molecules in the reaction center. Once the reaction center's chlorophyll is energized, it releases its excited electron to a primary electron acceptor molecule. This act of giving away an electron leaves the chlorophyll "oxidized" (having lost an electron) and initiates the flow of electrons through the thylakoid membrane.

The Splitting of Water (Photolysis)

The reaction center of Photosystem II, having lost an electron, now has a strong "electron hole" and needs a replacement. This is where water comes in. To replenish the lost electron, an enzyme complex within PSII splits a water molecule (H₂O) in a process called photolysis, which literally means "splitting by light." This reaction is one of the most brilliant designs in biology.

The splitting of a single water molecule yields two electrons, two protons (H⁺ ions), and one oxygen atom. The two electrons are used to replace those lost by the PSII reaction center, allowing the light absorption cycle to begin again. The protons are released into the thylakoid lumen, contributing to a proton gradient that will be used later. Since oxygen is unstable as a single atom, the oxygen atoms from two split water molecules combine to form a molecule of diatomic oxygen (O₂), which is then released as a waste product into the atmosphere—a "waste" product that is essential for most life on Earth.

The Electron Transport Chain (ETC)

The excited electron, having left PSII, embarks on a journey through an electron transport chain (ETC). This chain is a series of protein complexes embedded in the thylakoid membrane that pass the electron from one to the next, similar to a bucket brigade. As the electron is passed down the chain, it moves to progressively lower energy levels. The energy released during this downhill journey is not wasted; it is used by one of the protein complexes (the cytochrome complex) to actively pump more protons (H⁺) from the stroma into the thylakoid lumen.

This pumping action, combined with the protons released from the splitting of water, creates a high concentration of protons inside the lumen compared to the stroma. This difference in concentration is a form of stored potential energy, known as a proton-motive force or electrochemical gradient. Meanwhile, the electron eventually reaches Photosystem I (PSI). Here, it gets re-energized by another photon of light, giving it the final boost it needs to complete its task.

ATP and NADPH Synthesis

The final steps of the light-dependent reactions involve harnessing the stored energy to create the two key energy carriers. The high concentration of protons in the thylakoid lumen now flows "downhill" back into the stroma, but they can only pass through a specific channel protein called ATP synthase. As the protons rush through this enzyme, they cause it to spin, much like water turning a turbine. This rotational energy is used to attach a phosphate group to ADP (adenosine diphosphate), creating the high-energy molecule ATP.

Simultaneously, the re-energized electron from PSI is passed down a short, second electron transport chain. At the end of this chain, the electron is transferred to an enzyme that uses it to reduce the molecule NADP⁺, adding a proton (H⁺) to form NADPH. ATP and NADPH are the "charged batteries" of photosynthesis. They hold the captured light energy in a chemical form, ready to be transported to the stroma to power the next major stage of photosynthesis.

The Second Act: The Light-Independent Reactions (The Calvin Cycle)

With the energy now captured and stored in ATP and NADPH, the plant is ready for the second act: the light-independent reactions. This stage is also famously known as the Calvin Cycle, named after its discoverer, Melvin Calvin. While these reactions don't directly use light, they are critically dependent on the products of the light reactions (ATP and NADPH), so they typically happen during the day when the first stage is active. The primary purpose of the Calvin Cycle is to take carbon from the atmosphere (in the form of CO₂) and "fix" it into a stable, organic form—a sugar.

This process occurs in the stroma of the chloroplast, the fluid-filled space surrounding the thylakoids. The Calvin Cycle is a true cycle: it begins and ends with the same molecule, which is regenerated with each turn. It uses the chemical energy from ATP and the reducing power of NADPH to convert CO₂ into a three-carbon sugar called glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P). G3P is a versatile molecule that the plant can then use to build glucose, sucrose, starch, and other essential organic compounds. The cycle can be broken down into three main phases.

Carbon Fixation

The cycle officially begins when a molecule of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere enters the stroma. Here, the CO₂ molecule is "fixed" by being attached to a five-carbon sugar molecule called ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP). This critical reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme RuBisCO (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase), which is thought to be the most abundant protein on Earth.

The result of this fixation is an unstable six-carbon intermediate that immediately splits into two molecules of a three-carbon compound called 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PGA). At this point, the inorganic carbon from CO₂ has been successfully incorporated into an organic molecule. For every three CO₂ molecules that enter the cycle, six molecules of 3-PGA are produced.

Reduction

In the second phase, the newly formed 3-PGA molecules are converted into a different three-carbon compound: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P). This is the "reduction" phase because 3-PGA gains electrons. This conversion is a two-step process that requires energy, and this is where the products of the light-dependent reactions come into play.

First, each 3-PGA molecule receives a phosphate group from ATP (which becomes ADP), a process that "activates" the molecule. Then, the activated molecule is reduced by NADPH (which becomes NADP⁺), losing the phosphate group and becoming G3P. The ATP and NADPH have now "spent" their energy and are returned to the light-dependent reactions as ADP and NADP⁺ to be recharged. For every six molecules of 3-PGA that are reduced, six molecules of G3P are created.

Regeneration

This final phase is crucial for sustaining the cycle. Out of the six molecules of G3P produced in the reduction phase, only one is considered the net product of the cycle. This single G3P molecule exits the cycle and can be used by the plant to synthesize glucose (which requires two G3P molecules), starch for storage, or cellulose for structure.

The other five G3P molecules remain in the cycle. Through a complex series of reactions that require more ATP, these five three-carbon molecules are rearranged and converted back into three five-carbon molecules of RuBP, the starting material for carbon fixation. With RuBP regenerated, the cycle is ready to accept more CO₂ and turn again, continuing the process of building sugar from sunlight and air.

Factors Influencing the Rate of Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is not a process that occurs at a constant rate; it is a dynamic biological function that can be sped up or slowed down by various environmental conditions. Understanding these limiting factors is crucial for agriculture and for predicting how ecosystems might respond to climate change. The three primary factors that influence the rate of photosynthesis are light intensity, carbon dioxide concentration, and temperature.

Light intensity is perhaps the most obvious factor. In complete darkness, there is no photosynthesis. As light intensity increases, the rate of the light-dependent reactions increases, which in turn speeds up the entire process. More photons mean more electrons are excited, leading to more ATP and NADPH production. However, this effect is not limitless. At a certain point, the light-capturing machinery becomes saturated. The photosystems and enzymes are working at their maximum capacity, and further increases in light intensity will no longer increase the rate of photosynthesis. This is called the light saturation point.

Carbon dioxide (CO₂) concentration is another key determinant. CO₂ is the raw material for the Calvin Cycle. At low concentrations, the availability of CO₂ is the main bottleneck. The enzyme RuBisCO has nothing to work with, slowing the entire process down. As the CO₂ concentration increases, the rate of photosynthesis rises as RuBisCO can fix carbon more efficiently. Similar to light, there is a saturation point where increasing CO₂ levels further will not increase the rate because the enzymes are already working at full capacity or another factor (like light) has become the limiting one.

| Factor | Low Level | Optimal Level | High Level (Excess) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Intensity | Low rate (limiting factor) | High, efficient rate | Rate plateaus (saturation) |

| CO₂ Concentration | Low rate (limiting factor) | High, efficient rate | Rate plateaus (saturation) |

| Temperature | Low rate (enzymes are slow) | Peak rate (enzymes at optimal activity) | Rate drops sharply (enzymes denature) |

Temperature affects the enzymatic reactions of photosynthesis, particularly those in the Calvin Cycle. Like most enzymes, those involved in photosynthesis have an optimal temperature range at which they function most efficiently (typically 20-35°C for many plants). At low temperatures, the enzymes work very slowly, reducing the overall rate. As the temperature rises toward the optimum, the rate increases. However, if the temperature becomes too high, the enzymes begin to lose their shape and function—a process called denaturation. This causes a rapid drop in the rate of photosynthesis and can cause permanent damage to the plant.

Conclusion

From the capture of a single photon to the synthesis of a life-giving sugar molecule, photosynthesis is a symphony of precisely coordinated biochemical events. We've seen how it operates in two major acts: the light-dependent reactions, which convert solar energy into the chemical energy of ATP and NADPH within the thylakoid membranes, and the light-independent reactions (Calvin Cycle), which use that chemical energy to capture atmospheric carbon and build sugar in the stroma. This step-by-step breakdown reveals a process of breathtaking elegance and efficiency, perfected over billions of years of evolution.

The journey of energy from the sun to a leaf, and then into the molecules that form the foundation of our food webs, is the most important story on Earth. It is the process that terraformed our planet, filling the atmosphere with oxygen and paving the way for complex life. Every breath we take and every meal we eat is a direct or indirect consequence of this silent, constant work being done by the green world around us. By understanding how photosynthesis works, we gain a deeper appreciation for the delicate balance of our planet and the profound interconnectedness of all living things.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Why are most plants green?

A: Plants are green because their cells contain chloroplasts, which are filled with a pigment called chlorophyll. Chlorophyll is exceptional at absorbing light from the red and blue parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, but it is not good at absorbing green light. Instead, it reflects green light, which is why our eyes perceive leaves and stems as being green. This reflected light is the portion of the spectrum that the plant is not using for energy.

Q: Do all plants perform photosynthesis?

A: While the vast majority of plants are photosynthetic, there are some exceptions. A small number of plants are parasitic or myco-heterotrophic. These plants have lost the ability to photosynthesize and instead steal nutrients and energy by tapping into a host plant (like dodder) or by parasitizing the fungi that are connected to the roots of other plants (like the ghost plant). These plants typically lack chlorophyll and are not green.

Q: What is the difference between photosynthesis and cellular respiration?

A: Photosynthesis and cellular respiration are essentially opposite processes. Photosynthesis takes in carbon dioxide, water, and light energy to produce glucose and oxygen. Its purpose is to store energy. Cellular respiration, which is performed by both plants and animals, takes in glucose and oxygen to produce carbon dioxide, water, and chemical energy in the form of ATP. Its purpose is to release stored energy for the cell to use. In essence, photosynthesis builds the fuel, and respiration burns it.

Q: Can photosynthesis happen at night?

A: Photosynthesis as a whole process cannot happen at night because its first stage, the light-dependent reactions, explicitly requires light energy. However, the second stage, the Calvin Cycle (or light-independent reactions), does not directly use light. In theory, if a plant had a stored supply of ATP and NADPH from the day, the Calvin Cycle could continue for a short time in the dark. But in practice, the two stages are tightly coupled, and when the light reactions stop at night, the Calvin Cycle also ceases shortly after its supply of ATP and NADPH runs out.

***

Summary

The article, "How Photosynthesis Works: A Step-by-Step Breakdown," provides a comprehensive, 1500+ word explanation of the vital process of photosynthesis. It begins by defining photosynthesis and its foundational role in sustaining life on Earth through its simple equation: 6CO₂ + 6H₂O + Light → C₆H₁₂O₆ + 6O₂. The article then details the cellular location of this process, the chloroplast, and its internal structures like thylakoids and stroma.

The core of the article breaks photosynthesis into two main stages. The first, the Light-Dependent Reactions, is explained in four steps: (1) Light Absorption, (2) the Splitting of Water (Photolysis), (3) the Electron Transport Chain, and (4) the synthesis of energy-carrying molecules ATP and NADPH. The second stage, the Light-Independent Reactions (Calvin Cycle), is explained in three phases: (1) Carbon Fixation, where CO₂ is captured by the enzyme RuBisCO; (2) Reduction, where ATP and NADPH are used to create sugar (G3P); and (3) Regeneration of the starting molecule. The article also discusses how light intensity, CO₂ concentration, and temperature act as limiting factors. It concludes by reinforcing the profound importance of photosynthesis and includes a helpful FAQ section to address common questions.