Key Difference Between Monocot and Dicot Plants Explained

The difference between monocot and dicot plants is one of the first and most enduring distinctions students learn in botany. Understanding this difference helps identify plants in the field, explains how plants grow, and clarifies why some species behave differently in agriculture and ecology. In this article we’ll break down the key structural, developmental, and evolutionary contrasts between these two major groups, with clear, practical guidance for identification and application.

Fundamental Overview: What are Monocots and Dicots?

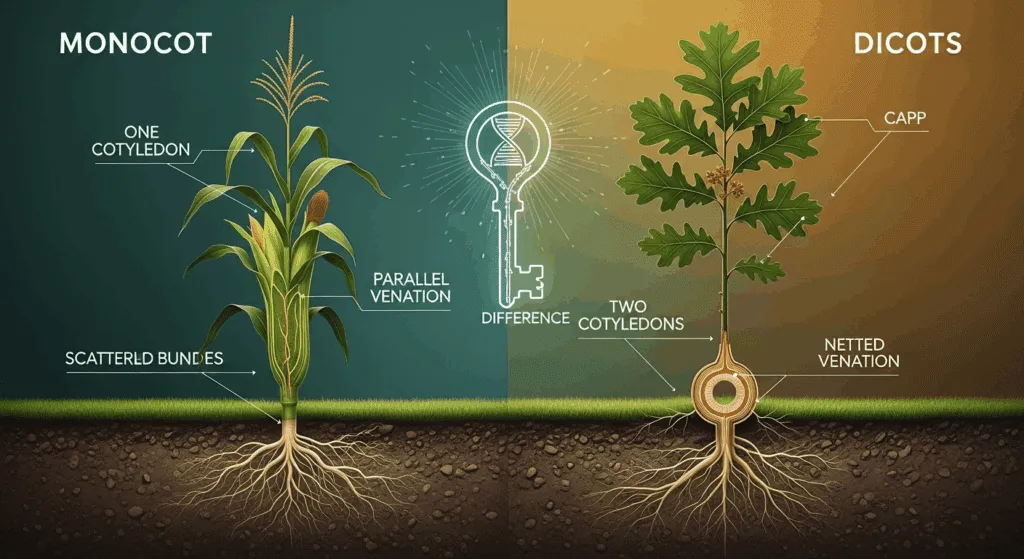

Monocots and dicots are informal terms historically used to separate flowering plants (angiosperms) based on the number of cotyledons (seed leaves) present in the embryo. Monocots typically have one cotyledon, while dicots have two. Although modern phylogenetics has refined how botanists classify angiosperms, the monocot–dicot distinction remains highly useful for practical identification.

These two groups diverged early in angiosperm evolution, and their morphological differences affect nearly every organ system: seeds, stems, leaves, roots, flowers, and even pollen. The distinction helps explain variations in crop management (for example, how grasses respond to mowing vs. legumes) and ecological roles (such as grassland vs. deciduous forest dynamics).

For SEO and clarity, note that people commonly search phrases like “monocot vs dicot characteristics,” “how to tell monocot from dicot,” and the exact phrase discussed here—difference between monocot and dicot plants—so this article addresses common queries and practical uses of these distinctions.

1. Definition and origin of terms

The terms monocotyledon (monocot) and dicotyledon (dicot) come from Greek: mono = one, di = two, and cotyledon = seed leaf. Historically, botanists grouped flowering plants into these two categories purely by cotyledon number. This classification worked well because cotyledon number correlates with many other structural differences.

Later molecular studies showed that “dicots” are a paraphyletic group (not all descendants from a single ancestor are included), which led to a refined set of clades (e.g., eudicots) in modern taxonomy. Despite this, for everyday identification and agricultural contexts the monocot/dicot framework remains practical and widely taught.

2. Why the difference matters

Recognizing whether a plant is a monocot or dicot helps predict growth patterns, responses to stress, and suitable cultivation techniques. For example, monocot grasses—like wheat and rice—have fibrous roots and parallel leaf veins, making them resilient to grazing and surface disturbance. Dicots—such as beans and tomatoes—commonly develop taproots and netted leaves, which influence irrigation, fertilization, and pruning decisions.

From an ecological standpoint, the distributions of monocot- and dicot-dominated habitats (lawns and grasslands vs. forests and shrublands) shape soil processes, fire regimes, and animal communities. Thus the monocot–dicot distinction is not just academic; it underpins practical choices in land management and crop breeding.

Seed and Embryo: Cotyledons and Germination

Seed structure is the most immediate and definitive feature used to separate monocots from dicots. The number and function of cotyledons affect early nutrient mobilization and seedling form.

Both groups store nutrients differently: some store in the seed endosperm, others in the cotyledons. These storage strategies influence how seedlings emerge and which part of the embryo becomes photosynthetic first.

Seed anatomy also influences germination behavior—some seedlings break the seed coat above ground, others below ground. Understanding these differences helps gardeners, farmers, and ecologists manage seedlings more effectively.

3. Cotyledon number and seed anatomy

Monocot seeds usually have a single cotyledon that often functions primarily to absorb nutrients from the endosperm and deliver them to the developing seedling. In grasses, the cotyledon is modified into structures such as the scutellum (in cereals) that facilitate nutrient transfer during germination.

Dicot seeds contain two cotyledons that typically act as storage organs and may become the first photosynthetic leaves in the seedling. These two seed leaves often store significant reserves and can be thick or fleshy depending on species, influencing how long seedlings rely on stored food before photosynthesis begins.

Because cotyledon morphology can vary, cotyledon count is most reliable when seeds or newly germinated seedlings are available. For mature plants, other traits (leaves, stems, roots) are used for identification.

4. Germination patterns and seedling traits

Monocot seedlings often exhibit a growth pattern known as hypogeal or epigeal depending on species, but many grasses show a protective sheath (coleoptile) that pushes through soil to protect the shoot. Roots emerge from a basal meristem area; cotyledon may stay below ground or be non-photosynthetic.

Dicot seedlings frequently produce a distinct above-ground pair of cotyledons that unfold and photosynthesize until true leaves take over. The presence of a central primary root (taproot) is common in dicots, giving seedlings immediate access to deeper soil moisture.

These differences influence planting depth and seed care: monocot seeds (e.g., corn) often require consistent shallow planting and surface moisture, while some dicot seeds may tolerate slightly deeper placement and variable moisture because of their stored reserves.

Vegetative Differences: Roots, Stems, and Leaves

Vegetative anatomy is where differences become obvious even without observing seeds. Root architecture, stem vascular arrangement, and leaf venation are key diagnostic traits.

Leaves and stems determine how a plant transports water, nutrients, and sugars, and they influence tolerance to physical damage, drought, and herbivory. Recognizing these patterns allows rapid field identification.

Below are the classic contrasts that students and practitioners use to tell monocots from dicots.

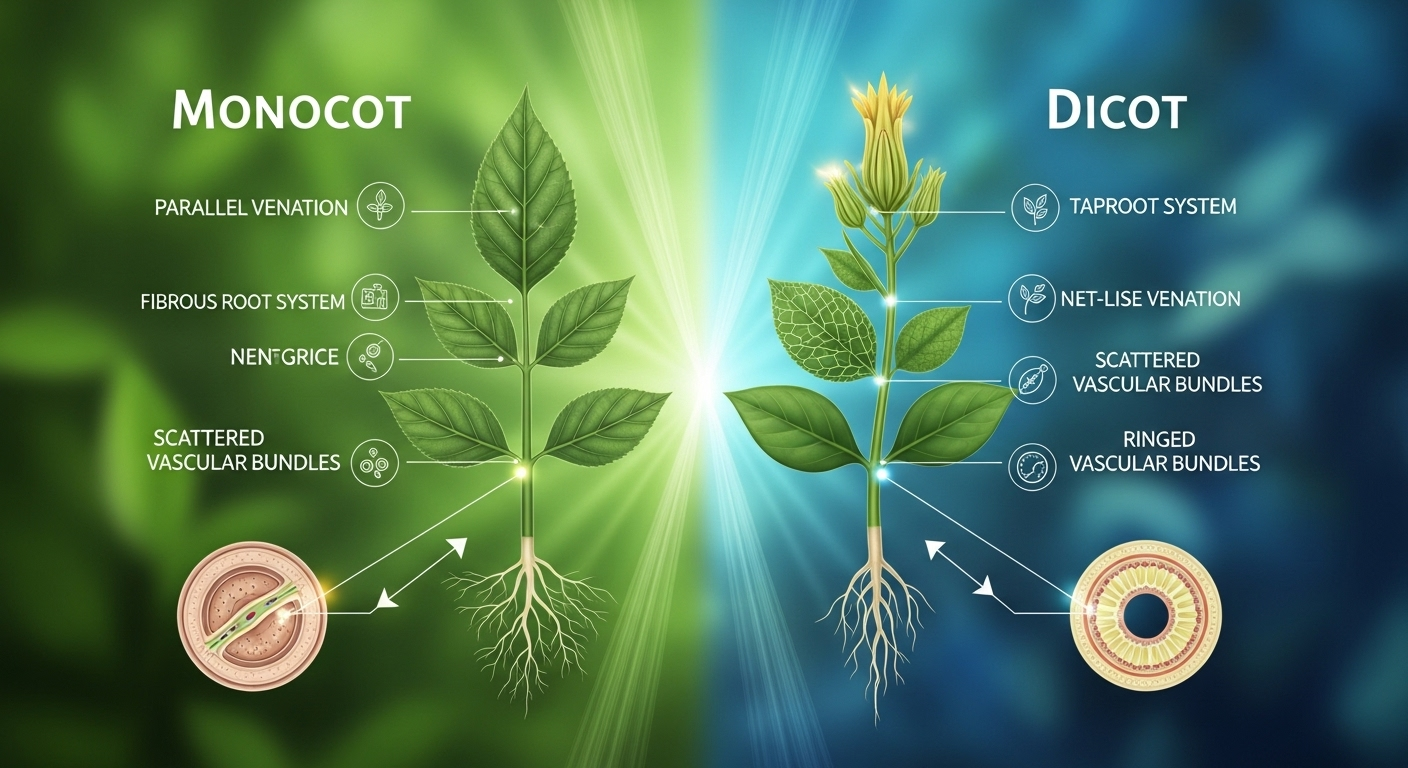

5. Root systems

Monocots typically develop a fibrous root system: many similarly sized roots arise from the stem base. This network stabilizes soil and is efficient at exploiting surface nutrients and moisture, which is why grasses recover quickly after cutting.

Dicots usually form a taproot system—a dominant primary root that grows downward with lateral branches. This allows access to deeper water and nutrients and can confer drought resilience. Many dicots also produce specialized storage roots (e.g., carrots).

Root anatomy differences also reflect secondary growth potential (discussed later): dicot roots more commonly undergo cambial activity leading to thickening in woody species.

6. Stem vascular arrangement

In monocots, vascular bundles (xylem and phloem) are scattered throughout the stem cross-section; they often lack a continuous ring. This arrangement typically precludes extensive secondary thickening and explains why most monocots are herbaceous (non-woody).

Dicot stems display vascular bundles arranged in a ring, which allows the formation of a vascular cambium—a meristem that produces secondary xylem and phloem—enabling trees and shrubs to grow thicker and form wood.

These anatomical arrangements affect how stems heal, how they transport nutrients, and their mechanical properties. For example, the ring-like organization in dicots is one reason many dicots form strong woody trunks.

7. Leaf venation and morphology

One of the easiest field cues: monocot leaves usually show parallel venation—long veins run roughly parallel from base to tip (common in grasses, lilies, palms). Dicots typically exhibit netted (reticulate) venation—a branching, web-like network of veins (common in roses, oaks, beans).

Leaf petiole attachments and leaf shapes also differ: monocots often have sheathing leaf bases that clasp the stem, whereas dicot leaves usually attach by a distinct petiole. Leaf arrangements (alternate, opposite, whorled) are more diverse in dicots.

These differences affect photosynthetic efficiency, transpiration, and leaf mechanical behavior—important considerations for crop selection and plant breeding.

Reproductive Traits: Flowers, Pollen, and Fruits

Flowers and reproductive structures often provide definitive monocot/dicot clues—particularly floral organ counts and pollen morphology.

Floral morphology influences pollination strategies, fruit types, and seed dispersal methods. Recognizing reproductive traits helps in systematics and in agricultural practices like hybridization and breeding.

8. Floral organs and symmetry

Monocot flowers commonly have floral parts in multiples of three (3, 6, 9), such as three petals and three sepals. Flower symmetry in monocots can be radial (actinomorphic) or bilateral in some groups.

Dicot flowers typically present floral parts in multiples of four or five (4, 5, 10). Many dicots show zygomorphic (bilaterally symmetric) flowers adapted to specialized pollinators like bees, birds, or bats.

Examples:

- Monocots: lilies (3 petals), orchids (3 petals and unique structures)

- Dicots: roses (numerous/five), peas (5 parts arranged for bee pollination)

9. Pollen structure and pollination

Pollen grains also differ: monocot pollen is often monosulcate (one furrow or pore), while dicot (particularly eudicot) pollen typically has multiple furrows or pores (tricolpate). These microscopic features are useful in paleobotany and palynology (pollen studies).

Pollination ecology varies: many monocots (like grasses) are wind-pollinated with small, non-showy flowers, whereas many dicots rely on insects or animals and evolve showy petals and nectar guides. These reproductive strategies affect breeding systems and gene flow.

Fruit types differ too—grains in grasses vs. pods, berries, and drupes in many dicot families—reflecting different dispersal mechanisms.

Secondary Growth, Evolution, and Exceptions

While the monocot/dicot model captures mainstream differences, there are important exceptions and evolutionary nuances. Some dicots lost secondary growth; some monocots form woody habits via different mechanisms.

Understanding the evolutionary context clarifies why strict rules sometimes fail and helps explain adaptive radiations and ecological success across habitats.

10. Secondary growth and woody habit

Most dicots (especially eudicots) can undergo secondary growth via a vascular cambium, producing wood (secondary xylem) and bark. This is the basis for tree trunks and shrubs and gives structural strength.

Most monocots lack a vascular cambium, so classical secondary thickening is absent. Yet some monocots (e.g., palms, some arborescent lilies) achieve a tree-like form through primary thickening or anomalous secondary growth—different anatomical pathways that mimic woody stems but are not true wood in the dicot sense.

These differences affect commercial uses: hardwoods come primarily from dicots, whereas many monocots (bamboos, palms) offer alternative structural materials with distinct properties.

11. Evolutionary context and exceptions

Modern phylogenetic analyses have reorganized angiosperm relationships. The term “dicot” is now largely replaced by clades like eudicots, which are a monophyletic group within the traditional dicots. Many older “dicot” families remain valid groups, but the big picture is more complex.

Exceptions—plants that don’t fit cleanly into the classic rules—highlight the dynamic nature of evolution. For instance, some dicot species may show parallel venation, and some monocots may develop secondary thickening. Therefore, rely on multiple characters for identification rather than a single trait.

Recognizing exceptions is crucial in taxonomic studies, breeding programs, and paleoecology where incomplete or fragmentary evidence may mislead.

Practical Identification & Economic Importance

Beyond theory, knowing how to identify monocots vs. dicots quickly is valuable in agriculture, gardening, ecology, and education. This section gives practical tips and outlines economic roles.

Farmers, horticulturists, and restoration ecologists use these traits daily to choose species, predict growth patterns, and manage ecosystems.

12. How to tell monocot from dicot: field tips

Quick checklist for field identification:

- Look at the cotyledons (seedlings): 1 = monocot, 2 = dicot.

- Observe leaf venation: parallel = monocot; netted = dicot.

- Count floral parts: multiples of 3 = monocot; multiples of 4 or 5 = dicot.

- Check root type: fibrous = monocot; taproot = dicot.

- Examine stem vascular pattern (if cut or cross-section is available): scattered = monocot; ring = dicot.

Use a combination of these features rather than a single trait for reliable identification under real-world conditions.

13. Agricultural and ecological significance

Monocots include major cereal crops (wheat, rice, maize), forage grasses, and many ornamentals (tulips, lilies), making them central to global food security. Their fibrous roots and rapid regrowth make them ideal for turf and erosion control.

Dicots encompass legumes (protein crops), fruit trees, vegetables, and many timber species. Their ability for secondary growth provides long-term carbon storage in forests and material for construction.

Both groups are essential: crop rotations often mix monocots and dicots to manage pests, enhance soil fertility (e.g., legumes fixing nitrogen), and optimize productivity.

Comparative Table: Monocot vs Dicot Traits

| Trait | Monocot | Dicot (Eudicot) |

|---|---|---|

| Cotyledons | 1 | 2 |

| Leaf venation | Parallel | Reticulate (net-like) |

| Vascular bundles in stem | Scattered | Arranged in a ring |

| Root system | Fibrous | Taproot common |

| Floral parts | Multiples of 3 | Multiples of 4 or 5 |

| Pollen | Monosulcate (often) | Tricolpate or multiple pores |

| Secondary growth | Rare; no typical cambium | Common; vascular cambium → wood |

| Typical examples | Grasses, lilies, orchids, palms | Beans, roses, oaks, sunflowers |

- Quick tips:

- Use a combination of leaf, root, flower, and seed traits.

- When in doubt, examine seedlings if possible.

- Remember exceptions—confirm with multiple observations.

FAQ — Common Questions (Q & A)

Q: How can I tell if a plant is a monocot or dicot without digging up roots?

A: Examine leaves and flowers. Parallel-veined leaves and floral parts in threes suggest a monocot. Netted veins and flower parts in fours or fives indicate a dicot. Seedling cotyledon number is definitive but requires a germinating seed.

Q: Are all grasses monocots?

A: Yes, all true grasses (family Poaceae) are monocots. They share traits like parallel venation, fibrous roots, and floral structures adapted for wind pollination.

Q: Can a dicot be woody while a monocot is always herbaceous?

A: While most dicots produce woody growth via vascular cambium, some dicots are herbaceous. Most monocots are herbaceous, but a few (palms, bamboos) achieve tree-like size through alternative thickening mechanisms—not true secondary growth as in dicots.

Q: Why did scientists move away from the dicot/monocot split in classification?

A: Molecular phylogenetics revealed that the traditional “dicots” do not form a single clade. Scientists now use clades like eudicots that reflect evolutionary relationships more accurately, while still using monocot/dicot distinctions for practical identification.

Q: What are common crop examples of each group?

A: Monocots: wheat, rice, maize, sugarcane. Dicots: soybean, bean, tomato, apple, cotton.

Conclusion

Understanding the difference between monocot and dicot plants gives you a practical toolkit for plant identification, agriculture, and ecological interpretation. While modern taxonomy refines the evolutionary story, the morphological contrasts—cotyledon number, leaf venation, stem vasculature, root type, floral organization—remain highly useful. Use multiple characters when identifying plants in the field, and remember that exceptions exist. Mastering these distinctions improves your decision-making in gardening, farming, restoration, and teaching.

Summary (English):

This article explained the key differences between monocot and dicot plants across seeds, vegetative organs, reproductive structures, and growth patterns. Monocots have one cotyledon, parallel leaf veins, scattered vascular bundles, fibrous roots, and floral parts in threes. Dicots (eudicots) typically have two cotyledons, netted leaf venation, ring-arranged vascular bundles enabling secondary growth, taproots, and floral parts in fours or fives. Practical identification tips, a comparative table, FAQs, and notes on exceptions and evolutionary context were included to make this information usable for students, gardeners, and agricultural professionals.